|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE CRITIC AS CRITIC |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Portfolio of Theatre and Book Reviews |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

_____ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

No 49 : MARCH

/ APRIL 2009 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wilde

theatre reviews appear here; Shaw reviews in Shavings;

all other theatre reviews in |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Exhibition

reviews and reviews of books relating to the visual arts now appear in our

new section VISIONS which is reached by clicking its symbol |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All

authors whose books are reviewed here are invited to respond. This page is edited by D.C. Rose and Anna

Vaninskaya. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

·

In an article for THE OSCHOLARS which she titled ‘Wilde on Tap’, Patricia Flanagan Behrendt, our American Editor, set out an agenda for our theatre coverage

that we

will try to follow. This article can

be found by clicking |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To the Table of Contents of this page |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

WILDE REVIEWS |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oscar Wilde / Hedwig Lachmann / Richard

Strauss: Salomé. Grand Théâtre de

Genève, Friday 13th February 2009 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Gothic Girl |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Salomé has disappeared

from the Geneva stage since 1983. In the 1983 production by Maurice Béjart

the splendid Julia Migenes-Johnson embodied the ideal combination for this

role: a world-class opera singer and a graceful dancer. Her performance

became history. Already in the season 1966-1967 another striking singer, Anja

Silja, had been a revelation in the production of Wieland Wagner at the Grand

Théâtre. A heavy heritage for the

German soprano Nicola Beller Carbone, who appeared for the first time in the

Grand Théâtre de Genève. Since 2003 she has performed the role several times

in productions by Michael Schulz, Robert Carsen and others. During the years

Nicola Beller Carbone grew in the part; she showed in Geneva an impressive

Salome. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Richard

Strauss turned the biblical story into an opera which caused a scandal when

it was first performed in 1905. German director Nicolas Brieger revisited

the opera by the Bavarian composer at the Grand Théâtre in Geneva. Bieger

presented a production that seemed intensely and profoundly interpretive,

almost all interpretation. Bieger did not choose for beauty ,rather for

offending and showing all the evil in the human nature. Bieger: ‘The opera

tackles a very sensitive subject. It evokes something we have never accepted

in our culture’s history. It is about incest.’ Especially in the performance

of the 10-minute ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’ the director goes his own way. In

an enormous sac of beige tricot Salome wiggles without grace, soon

accompanied by Herod. Result is a lascivious ballet, a rather ridiculous

image. At the end Salome and Herod leave their cocoon, Salome in petticoat

wearing the waistcoat of her stepfather, Herod himself stripped to the waist. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bieger’s

production, with sets by Raimund Bauer and lighting by Alexander Koppelmann,

uses a contemporary setting. In the background is a slaughterhouse, in the

foreground a dirty terrace. On the first floor in the background is the

palace of Herod. Brieger describes the decadence of Salome’s environment by

scenes of abuse and violence: not only

are the guests of Herod throwing rubbish and glasses from the balcony to the

central terrace, they are also raping naked girls. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Andrea

Schmidt-Futterer, who designed the costumes, dressed most of the characters

in modern European style clothing, save Jokanaan. Herod’s soldiers are real

contemporary soldiers, the Jews have the orthodox corkscrew curl dangling before each ear, Herodias is in

evening dress, Herod in a dark suit. Salome is dressed as a gothic girl and

seems like a groupie of some obscure gothic band. From the dance of the seven

veils she is in petticoat. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nicola

Beller Carbone’s Salome is a young woman fascinated by the effect she has on

people. The leering men of Herod’s court – inclusive Herod himself – are

constantly ogling her. Salome herself is exasperated by Jokanaan. We first

hear him from the underground cistern, and see him later when he appears and

is taunted by Salome. In the final scene, some 15 minutes of musically

voluptuous necrophilia, when Salome kisses Jokanaan’s severed head, Nicola

Beller Carbone sounded and acted possessed. It was a vocally blazing and

dramatically shattering portrayal of the title role of Strauss’s opera. The

fascinating personality of Nicola Beller Carbone makes us forget the other

fine performances, as bass-baritone Alan Held in a strong debut at the Grand

Théâtre, the bright-voiced tenor Kim Begley in a dynamic portrayal and Hedwig

Fassbender as Herodiade. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gabriele Ferro conducted the Orchestre de la

Suisse Romande. Sad to say this was not their best

performance. Was it the confused conducting style of Ferro which caused the

orchestral weakness at the opening night? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All in all

an interesting production, with a splendid Nicola Beller Carbone. She really

deserves a place among the most memorable who have tackled the role in the

last half-century. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Grand Théâtre de Genève 13th –

28th February 2009 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

·

Tine Englebert is Music Editor of THE OSCHOLARS. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Approaches to the Teaching of Oscar Wilde, ed. Philip E. Smith II (New York: The Modern Language Association

of America, 2008). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Philip E. Smith provided some of

the most important intellectual resources in Wilde scholarship with his

edition of the Oxford Notebooks. In

this new volume he has provided a very different form of academic resource,

focusing on the variety of ways that pedagogic practice has disseminated

Wilde’s work. The majority of the essays are written by academics working in

the American system, and the approaches are often different to the British

text per week model, but the intellectual and cultural contexts mobilized

here are generally international in scope. Smith divides the book into a

series of sections which are largely decided by genre, with drama being

dominant within a wide remit that includes the teaching of the trial, the

critical essays and the short fiction. For the purposes of this review I

shall separate the volume into wider treatments of methodology and course

construction, treatments of drama, and then a general consideration of the

fiction and criticism which is concerned in particular with the relative

claims of contextual and theoretical pedagogy. Unsurprisingly, Wilde’s

sexuality is a dominant contextual and theoretical concern, but the

collection traduces multifarious critical regions, passing through Ireland,

Nietzsche, and synaesthesia, Ibsen, Hollywood, and deconstruction. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Course Construction and Pedagogic Method |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The first essay, Bruce Bashford’s

‘The Critic as Student: An Argumentative Approach’, promotes a student

centered interpretative method which encourages students towards effective argumentation.

What Bashford describes is a largely common sense approach to what most of us

do intuitively week to week, but his treatment of class discussions gives a

detailed sense of how arguments are constructed, of inference and dialectic

in action. He also gives an example of how he constructed and revised very

detailed essay questions according to student response. His persistent

demands for evidence from his students are clearly rigorous, but they also

suggest a legal analogue; this is as much the student on trial as the student

as critic/artist. This is of course a fundamental aspect of the educational

system, but when the subject is Wilde the trial analogue cannot help but

provoke questions about power and discourse, institution and authority. This

volume is not meta-critical or theoretical in this sense; the ideology and

conditions of academic authority are not questioned, in spite of Wilde’s

anarchism, but it does provide many useful ways of approaching Wilde’s work. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The majority of the essays treat

individual works or a small selection, but some notable exceptions provide

more ambitious course plans. One of the most inspiring essays in the

collection is Philip E. Smith II’s account of his course on Wilde and the

1890’s, which positions Wilde’s work in terms of an impressively wide range

of European artistic and intellectual contexts: as well as the familiar and

necessary contexts for British Aestheticism (Ruskin, Pre-Raphaelitism,

Arnold, Pater), Smith includes Nietzsche’s The Genealogy of Morals, Ibsen’s Ghosts and Hedda Gabler, passages from Nordau’s Degeneration, and stories from Daughters of Decadence. The inclusion

of Nietzsche is significant: Smith sets the final chapters of the Genealogy alongside Dorian Gray and the critical

dialogues, in order to focus ideas about art as lying, the will to power, and

the relationship between art and morality. This is the real sign of the

intellectual ambition of this course, since it suggests a pedagogical

practice which is not bound my historicist and contextual orthodoxy. This is

not to say that Smith’s course is not clearly alive to the extensive

contextual resources of Wilde scholarship; these are clearly, and

necessarily, important for his teaching of the trial and De Profundis towards the end of his course. But the use of

Nietzsche allows for a different form of comparative philosophical and

aesthetic questioning. In my experience, which is largely limited to British

higher education, this kind of pedagogic method is very common in the

teaching in modernism, and ubiquitous in the study of contemporary

literature, but seems to have become outlawed in Victorian Studies. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Equally inspiring is Alan

Ackerman’s account of teaching The

Importance of Being Earnest on a course on Western Drama. Although the

account is ostensibly focused on a single text, the remit is actually much

broader. Ackerman suggests that students interrogate the notion of form,

making a useful transition between notions of dramatic form since Aristotle

to the idea of social or ceremonial form stated in The Picture of Dorian Gray, where Dorian reiterates Henry’s

thoughts about ‘the canons of good society’ in which ‘form is absolutely

essential’. This is just the kind of insight that we would hope for from an

essay on teaching, since it reminds of us an issue of which we should be well

aware as scholars, but which provides a simple but effective template for a

class discussion of the play. Ackerman’s subsequent discussion of Earnest maintains a compelling focus

on the tensions between form and freedom – the pressure to live up to formal

conventions, and the relationship between the formal contrivances of the well

made play with the way that characters shape, or fail to shape, individual

destiny. This involves diverse and illuminating intellectual contexts –

Coleridge on organic form, Bergson’s ideas about automatism, ceremonial and

the comic, Hegel and Plato’s contrary ideas of form and development– which

are synthesized into a general contrast between mechanical and organic

conceptions of form. This might seem to some like an excessively weighty and

earnest theoretical architecture for the reading of Earnest, but Ackerman makes it exciting by demonstrating how

relevant it is to the breadth of Wilde’s critical and dramatic texts. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Teaching Wilde’s Drama |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is notable in this volume that

the more comparative and theoretical approaches tend to emerge from courses

where ‘modernity’ or ‘modernism’ is the primary period remit. Francesca Coppa

begins her essay on the teaching Wilde’s drama with the information that she

will invariably teach Wilde on courses with ‘modern’ in the title, in this

case Modern Drama, but notes the

difficulties that Wilde’s historical position causes for teaching. In between

Victorian and modern, Wilde demands that we are acquainted with a variety of

C19 forms; melodrama, naturalism, the well-made play; whilst at the same time

his epigrammatic and paradoxical play with morality and convention calls to

modernist and post-modernist intellectual paradigms. In approaching Wilde’s

Victorianism and modernity Coppa, like Smith, uses Ibsen as an important

comparative focus, cleverly following William Archer’s comment on Salome as ‘an oriental Hedda Gabler’

to stage a comparison between the different modernities of the two plays, as

well as Strindberg’s Miss Julie. She

subsequently frames a different kind of theatrical modernism, based on

political realism, in a comparison between An Ideal Husband, Ibsen’s A

Doll’s House, Strindberg’s The

Father, and Shaw’s Candida.

This leads to a detailed account of her teaching of Lady Windermere’s Fan, which suggests that many of Wilde’s

strategies are familiar to students through the cultural arena of post-modernity;

‘poaching’ or mimicry, parody and self-conscious melodrama, and ironic

reference in which complicity and subversiveness are often indistinguishable.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This still leaves the question

of what intellectual contexts we use to articulate Wilde as post-modernist avant la lettre. If that is to be a

pedagogic method, it might be argued, then it deserves to be followed through

in earnest. Do we set students to read

Butler on performativity, Bhabha on mimicry, Jameson on pastiche, with the risk

that we merely reiterate somebody else’s course on post-modernist fiction and

theory, or do we use the usual Victorian suspects? Some approaches to the

drama in this volume are resolutely Victorianist; Kirsten Shepherd-Barr’s

teaching of A Woman of No Importance is

closely focused on C19 theatre history and the conventions of melodrama,

although once again, Ibsen’s modernity is a key comparative context. Sos

Eltis’s essay again promotes the comparison with Ibsen and Shaw, but within

the context of a very broad survey of C19 drama, including Pinero, Jones and

Granville Barker. The emphasis is still on the traditional period-based

contextual course, and although Eltis’s essay does mention legacies such as

Joe Orton, the general impression of this book is a rather uniform tendency

in the teaching of late C19 drama. A contrasting approach is Robert Preissle,

who focuses on ‘transgeneric’ and ‘transhistorical’ reception issues. Filmic

adaptation is central to his genre approach, but the inevitable translation

this effects leads in to his questions about the historical dimensions of

teaching Wilde: to what extent can we transpose the text from the Victorian

to the contemporary, and conversely, to what extent can we transpose a

contemporary cultural or theoretical paradigm on to Wilde’s texts? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The contextual method also tends

to dominate in the series of essays on Salome,

which receives extensive and welcome attention. Ezsther Szalczer describes a

theatre history seminar she taught which focused on the symbolist theatre of

the 1890’s. This allowed for an extraordinary 6 weeks on Salome alone, examining biblical and literary sources, theatre

history, Beardsley’s illustrations, dance and operatic incarnations. Group

projects are assigned which look at the work ‘not as an isolated piece but as

an integral work of a cultural and historical process’; one group, for

example, works on filmic versions of the play in relation to the development

of the early twentieth century Entertainment industry. In general, the essays

on Salome suggest how a profusion

of classroom possibilities can emerge from one text through interdisciplinary

work which properly uses cultural and academic resources. Joan Navarre begins

with group discussion of relevant Bible passages, then examines dramatic

structure in detail with a continual focus on gaze relations, using Laura

Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’. Petra Dierkes-Thrun is lucky

enough to have significant filmic resources for her class, using amongst

others the Bryant/Nazimova camp masterpiece and the inspired foolishness of

Ken Russell’s Salomé’s Last Dance.

Her approach is properly multi-media, offering students a taste of

Maeterlinck’s drama, Mallarmé’s poetry, Huysmans ekphrasis of Moreau, and a variety of Symbolist painters. This is

surely the best approach to the formal avant-gardism of Salome, and Dierkes-Thrun’s teaching is primarily orientated by

the Symbolist poetics of synaesthesia. Beth Tashery Shannon gives a more

detailed comparative treatment of Symbolist sources, also making Moreau,

Huysmans and Mallarme central. This approach is so dominant in this section

of the book that there is some repetition across the essays, and in this

sense we might have hoped for a greater diversity from the volume. A more

theoretically focused argument is provided by Samuel Lyndon Gladden, whose

classes are orientated towards a specific and interesting argument about the

erotic and pornographic regimes of the play. Gladden brings together the

religious and erotic spheres through the concept of incarnation, and

distinguishes both these dimensions from the raw materiality of the

pornographic. It’s not entirely clear how he illustrates this distinction to

students with the considerable visual and filmic material at his command, but

the approach is clearly ambitious. What is striking about many of these

accounts from a UK perspective is just how much classroom time they have to

give to a work which rarely receives a full seminar worth of discussion in

British English departments. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Theory and Fiction /

Translation and Context |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The essays on the theory and

fiction are perhaps more diverse in methodology than those on drama. Joe

Law’s brief but useful essay on teaching Intentions

focuses on ideas of personal development, individualism and the tendency

towards self-multiplication in decadent self-fashioning. Students are given

sections from Plato’s Republic on

education and mimesis – clearly sources for Vivian’s manifesto’s in ‘The

Decay of Lying’ – and passages from Arnold and Pater relevant to ‘The Critic

as Artist’. The main motivation here is to present Wilde’s critical work as

the culmination of a course on Victorian on non-fictional prose, but the

discussion of the critical dialogues in relation to Dorian make it apparent that, perhaps against Law’s intentions,

Wilde’s critical masks, ‘Gilbert’ and ‘Vivian’, might be more profitably

studied in a trans-generic course on the mask in fiction, drama and

criticism. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

David Rose’s approach to the

shorter fiction is informed by a broad combination of material and cultural

contexts, following an inter-textual web from the tales to fin-de-siècle

gothic works, then to criminal London. Rose is essentially provoking his

students to become detectives: he enacts a move from historical to geographic

context, encouraging students to use cartographical archives and follow a

series of elliptical name and address references in a Holmes like manner.

This leads in to a consideration of the wider tradition of London writing.

This spatial focus is equally suggested by the title of Shelton Waldrep’s

essay, ‘Gray Zones’, which is primarily concerned with the Gothic contexts

for Dorian Gray. In the context of

a course on the Gothic in C19 Fiction Waldrep bases his classes on the shift

from the fear of ‘reverse colonization’ to the discourse of degeneration, and

moves from the cultural anxieties mobilized by the gothic mode to a

consideration of sexuality. Waldrep problematizes definitive identifications

of Dorian as a gay text, and the

move from the gothic to sexuality works well; if students are thinking about

the gothic uncanny and concealment they will better be able to articulate

whether Dorian is a text about the

closet, and they will also be alert to the ways that its shifts between

realism and romance inflect the representation of desire.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nikolai Endres, in contrast,

teaches Dorian as a definitively

‘gay’ text (his quotation marks) by asking his student’s the simple question:

‘If you wanted to convey homoerotic activity but were prevented from speaking

it out, how would you do it?’. He subsequently asks students to put Dorian’s

sexuality to the test, according to Victorian images of effeminacy and

homosexuality, and his seminar proceeds by teasing out the queer

undercurrents of a series of material and cultural contexts, including

dandyism, Roman Catholicism, flowers, and, charmingly, bumble bees. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jonathan Alexander’s intention is

to teach students to queer the text through film, illuminating methods of

suppression and closeting by reference to the more spectacular medium. He

outlines the different sexual politics of three filmic adaptations, from

1945, 1970 and 1983, using the most recent movie, The Sins of Dorian Gray, as an example of narrative transvestism,

since Dorian is now a female actress and her jilted lover, Stuart Vane, a

young male musician. This account is in some ways representative of the

interpretative decisions involved in teaching Dorian, precisely because Alexander’s pedagogic intentions are

not necessarily borne out; although he reads The Sins as a queering of Dorian,

the effect of his account of the various films is to highlight the text’s

extraordinary translatability across sexual and gender identification - its

exemplary capacity to be grafted and recontextualised. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These questions of historical

translatability are crucial to the teaching of sexuality and identity in

Wilde’s work. Heath A Diehl’s brings them into focus in his essay on teaching

De Profundis and Moisés Kauffman’s

Wilde trial play, Gross Indecency,

and Frederick Roden uses the same texts to teach the complex relationship

between religion and sexuality, with the humanist aim of promoting

tolerance. Diehl prescribes an

‘earnest’ mode of reading which is attentive to the historical specificity of

gay experience in the late nineteenth century and afterwards, but also

comparative in a trans-historical treatment of coming-out narratives. Wilde

is taught in a four-week section of a course on ‘Growing Up Gay/Lesbian’,

which is Diehl’s adaptation of a more general course on ‘Growing Up’, which

previously focused on the bildungsroman.

The process of adaptation and translation itself is in many ways

representative of Aesthetic and Decadent self-fashioning, but these accounts

of sexuality in Wilde’s work intrinsically raise questions about the

translatability of experience – between historical frameworks and different

sexualities. Historicists frequently give the impression that the context of

production is the only valid focus for reception, so that reading mirrors

that kind of archeological practice that Wilde himself prescribed, following

Godwin, in his piece on Shakespearean production, ‘Shakespeare and Stage

Costume’. It is well for us to remember that Wilde moved away from this

method radically, particularly in ‘The Portrait of Mr W.H.’, where he

recontextualised Shakespeare’s Platonist love narratives in an extraordinary

feat of trans-historical imaginative scholarship. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The one essay on the teaching of

‘Mr W.H.’ in this volume uses the complex textual conditions of the work as

an opportunity to introduce students to post-structuralist theories of

textuality. Jarlath Killeen uses Barthes on authorship and Derrida on

logocentrism to illuminate the problems of reading that are integral to

Wilde’s forged narrative of Shakespearean interpretation, and he proceeds to

contextualise these hermeneutic questions in Victorian biblical scholarship,

following his own research on Aestheticism and Catholicism. This is a

rigorous and impressive method, and unusual in its combination of the

contemporary orthodoxy of contextual scholarship with the deconstructive

approach that historicism has largely replaced and repressed in the study of

Victorian literature. One can imagine how Killeen’s student’s are challenged

by these reading experiments, but one thing that is lost from this highly

specific approach is the theatricality which Wilde promotes as intrinsic to the

narrative of Mr W.H., but also to the history of Western culture. In this

sense the more relevant Derrida text would be Dissemination, which is concerned precisely with the Platonic

rejection of mimesis and the ways that this is overturned by fin de siècle

theatricality – the model of this theoretical subversion being a morally

perverse mime text by Mallarmé. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is interesting to compare

Killeen’s deconstructive approach with that of Joseph Bristow, one of the

godfathers of contextualism. In his essay on The Ballad of Reading Gaol, Bristow builds up an extremely

detailed set of contextual resources; after a harrowing account of Wilde’s

incarceration he looks at comparable works by Henley and Kipling in order to

frame the question of The Ballad’s

conditions – is it propaganda or poetry? What are the consequences of the

combination of realism and romance that so discomforted Wilde himself?

Bristow frames these questions with such detail that it’s not easy to see how

the information would inform seminar practice, but this is closer to the

format of an original research essay than a pedagogic survey. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Clearly some texts and cultural

phenomenon suit a context-of-production method more than others. If literary

texts are always translatable, offering us infinite possibilities to graft

them onto alternate contexts, then Wilde’s great achievement as a performance

artist – his own life – is historically specific. Melissa Knox uses a

biographical template to teach Wilde, in this case to German students who are

less familiar with British and Irish cultural contexts, and Neil Sammells

teaches the complexity of Wilde’s relation to Ireland. Both of these essays

suggest an awareness of Wilde’s performativity within specific historical

conditions. Sammells asserts that ‘Irishness was for Wilde a form of

discursive play and performance’, and the tension between performative play

and organic identification in this account might be loosely connected between

the tension in Knox’s teaching between a confessional Wilde, whose ‘very name

is compiled of heroes of ancient Ireland’, and the Wilde of stylized Neronian

reconstruction and elliptical surfaces. One would hope that these contexts

inform a wider discussion of the ways that Wildean texts mobilize and

complicate depth-models of personality and Victorian ideas of self-culture.

In this light, S.I.Salamensky’s short essay on the libel trial is useful for

the numerous questions it focuses around the trial, many of which are

generally applicable to much of Wilde’s work – the nature and use of the

epigram, the location of sexual identity, the nature of the pose and the

relationship between seeming and being. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These familiar formal and

theoretical questions were all integral to late Victorian literary and

aesthetic discourse. Perhaps the most surprising aspect of this collection is

that, in spite of all the varying contextual and thematic resources it

documents, it actually pays relatively little attention to Aestheticism as a

specific late-Victorian discourse about the fate of art in society. Whether

we see Aestheticism as a genuine cultural movement or as a hybrid set of

discourses given retrospective coherence, there is no doubt that the young

Wilde saw it as the former. Joe Law’s essay on Intentions and Philip Smith’s course survey are amongst the few

pieces to pay much attention to the discursive presence of Pater and Ruskin

in his work. The one essay to promote Wilde as apostle of Aestheticism is

Nicholas Ruddick’s account of teaching the fairy tales, which uses ‘The Happy

Prince’ to articulate Wilde’s ideal of beauty and critique of utilitarianism.

He briefly suggests ways in which the tales would lead into a consideration

of belated Romanticism, the Christ figure of ‘De Profundis’, and that

marginal but representative figure of Aestheticism, the Young Syrian in Salome. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

That it should fall on one short

piece to articulate the claims of Wildean Aestheticism is demonstrative of

the extraordinary proliferation of pedagogic approaches to Wilde in the

contemporary academy. A symptom of this range is that an impressive and

useful collection such as this should be lacking in what may would regard as

fundamental to the teaching of Wilde. This is surprising when its editor has

done more than anyone to promote the intellectual coherence of Victorian

Oxford in the 1870’s. Wilde considered The

Renaissance his ‘golden book’ and it has always been fundamental to my

approach to teaching Wilde, but conversely, I should accept any challenge to

this habit; the teaching of Aestheticism should be deliberately diverse,

‘never acquiescing in a facile orthodoxy’ of the more obvious contexts. In

this light, it might have been an interesting subject for this collection to

examine the relations between student learning and the construction of

pedagogic authority in the light of Wilde’s articulation of anarchism in ‘The

Soul of Man under Socialism’. But there is room for this in other forums.

Smith’s volume is an ideal beginning for us to reflect and expand on our own

teaching practice. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Redgrave performs

Wilde’s De Profundis at the Irish

Cultural Centre in Paris |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Corin Redgrave, the prominent English actor

and activist graced the stage at the Irish Cultural Centre in Paris in

February. Redgrave performed Oscar Wilde’s love letter ‘De Profundis’

to a packed room. The letter, which was written by Wilde while he was

in prison, is dedicated to his lover Lord Alfred Douglas. It is a

tell-all of Wilde’s profound love and passion for Douglas, but it is also

laced with regret, anguish, and resentment. At times sentimental, at

times sarcastic, but always profoundly insightful, this letter takes us to

the heart of a broken man who has fallen from grace. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

From the beginning of Redgrave’s

performance, the audience was emerged into the harsh truth of Wilde’s

suffering and loss. During the 50 minute monologue I felt pity for

Wilde as he recounted the selfish and indifferent attitude of Lord Alfred

Douglas; however, at the same time, I felt as though I have been in his place

before, too. As have many of us. For, as Wilde knew all too well,

nothing is fair in love. Perhaps this is what makes this piece a true

love letter. And Redgrave’s thoughtful performance takes you to that

place, so deep and buried in your heart. Redgrave managed to make the

audience cry and, surprisingly, laugh – just as Wilde would have done.

On a lonely chair, with paper and pen in hand, Redgrave captured the essence

of a man, once the darling of Bourgeois society, now alone in a prison cell

writing one of the most beautiful and tragic love stories of all time.

But ironically, and therefore so Wilde, that is love: sometimes beautiful but

more often dirty. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Redgrave received a standing ovation as he

was helped off the stage. He left the audience wanting more, if only to

discuss the piece with the legendary actor. However, parting in silence

and humbly is how the dignified Wilde would have wanted it. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

·

Saralinda Abitbol is an English teacher at Sciences-Po Paris and a freelance

journalist. She is currently working on a piece about Oscar

Wilde's Paris. For Sondeep Kandola’s

review of Redgrave’s De Profundis

at the National Theatre in London, click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chris Coleman directs The Importance of Being Earnest at Portland Center Stage |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

24th February-29th March 2009 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The

programme touts the play as ‘A Wildean frolic… in three acts’, and though it

essentially is as advertised, Artistic Director Chris Coleman’s treatment of Earnest is clearly more serious than

trivial. The setting is thoroughly Victorian in mood and manner and this

comes as a welcome surprise. I have seen Wilde staged in and out of period

and though it is amusing to see Earnest

queered, such as the KAOS Theatre’s burlesque interpretation notably

does, it is also good to remember that Wilde’s lines undermine the age in

which they were written in Worthing (1894) and staged in London (1895). Earnest is a mirror into which Wilde’s

contemporaries saw a reflection of themselves just as today’s audiences do.

The beauty and brilliance of depicting Earnest

true to period, paying particular attention to character, diction, plot and

costume, is that it reinforces the fact that it does not require

embellishment in order to appeal to a 21-century audience, and Coleman’s

production justly qualifies this point. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

James

Knight, as Algernon, instantly captivates the audience as he steps on stage

from the adjoining piano room into the morning-room in a rich navy satin

smoking jacket. Lane (Todd Van Voris) is tidying the tea-cart and, in what

appears to be the only obvious deus ex

machina of the production, tosses a brassiere off stage. Knight’s mannerisms and delivery are

impeccably ‘Algernon’s’, as we might ideally imagine him, from the

script. Indeed, he is the most

convincing Algy I have seen and this is apparent in the smallest details as

well, such as the distinct way he fondles and then pinches a pink rose from

the bouquet to wear in his button hole. This, of course, foreshadows Cecily

(Nikki Coble) as does the entire set, which is framed in pink roses. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There

are several fine points to this production, but one that must be mentioned

outright is costume design, coordinated by Jeff Cone. Cone’s use of texture

and colour to emphasise character and mood, city and country, parallel

Coleman’s artistic vision and attention to detail. As mentioned, Algernon

enters in a smoking jacket which underscores his languid demeanor and also

serves to contrast Jack, who enters fully dressed for ‘business’ though we

know he is in town for ‘pleasure’, or, rather, to propose to Gwendolen.

Algernon’s quip ‘I thought you had come up for pleasure? I call that

business’ received an applause, and I believe this is a testament to the

parallel form and structure of the play that scaffolds Knight’s effective

elocution, balanced delivery, and stage presence. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Throughout

the play, it was moments such as this where Knight radiated precisely because

he delivered the lines fluidly and with the right amount of emphasis rather

than exaggeration. The same can be said of Jack’s (Matthew Waterson)

interplay with Algy, especially his well-crafted agitation with Algy’s

apparent disregard for the serious nature of marriage, or the stance one must

assume in order to appear ‘earnest’. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lady

Bracknell (Jill Tanner) and Gwendolen Fairfax (Kate MacCluggage) enter in

gorgeous gowns complete with feather hats, Gwendolen in pink and Lady

Bracknell in bronze. Again, Cone’s design choice conveys style and position

without seeming overtly ostentatious. Likewise, Lady Bracknell was not the

overbearing ‘gorgon’ that I have seen in other productions of Earnest, though I admit that I

typically look forward to her dominating the stage. However, I was pleasantly

surprised to find the ‘softer’ Bracknell alluring and suggestively

aggressive, which, after rethinking my expectations, is in many respects a

bold move because the lines are not overacted. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ahh,

Miss Prism (Sharonlee McClean) and Chasuble (Tim True), where to start: the

underlying sexual tension was enhanced, and though tension is evident in the

script, by the Second Act I was beginning to expect downplaying, or at least

subtle undertones rather than ‘reckless extravagance’ in ones so old. I

suppose this was the point, as the mirroring effects throughout were keenly

interpreted. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Without

hesitation, the muffin scene in Jack’s country garden at the close of the

Second Act was delightful. Again, I attribute this to Knight’s impeccable

skill and presence as Algernon and the interplay with Jack (Waterson) who was

consistently agitated with Algy’s ‘absurd’ behaviour at critical times: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jack: How you can sit there, calmly eating muffins

when we are in this horrible trouble, I can’t make out. You seem to me to be

perfectly heartless. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Algernon: Well, I can’t eat muffins in an agitated

manner. The butter would probably get on my cuffs. One should always eat

muffins quite calmly. It is the only way to eat them. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This

exchange highlights the relation and difference between Jack and Algy rather

tellingly, and though I have seen it performed ‘well’ in other productions,

this scene was by far my favourite, and gauging the audience’s reception, I

would say they definitely concurred. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Part

of the brilliance of the production must also be attributed to the stage

design and clear acoustics. Balanced sound resonates at the Gerding Theatre

and this was a main concern for the architects and sound technicians when

converting the 19th century Portland Armory into a modern theatre

in the heart of Portland’s Pearl District. Of course, lighting and ambience

contributes to the aesthetic impression and experience as well and I believe

any theatergoer in Portland would tell you just how unique the Gerding is. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Overall,

PCS’s The Importance of Being Earnest was

a pleasure to see. I have a newfound respect and appreciation for balanced

delivery and subtle undertones. During

the second intermission between the Second and Third Act I ordered a

Gwendolen inspired Champagne with Chambord and mingled a little with the

audience. I asked the couple standing next to me what their initial

impressions were, and in line with my own thoughts, they ‘loved’ Algernon’s

performance. James Knight holds an M.F.A. from the University of Missouri

Kansas City and though he has performed widely at venues across the nation in

roles ranging from Marc Antony in Julius

Caesar to Achilles in The Iliad,

this was his first appearance in Portland and he performed Wildely as

Algernon to a delighted audience. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cast of Characters: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cecily |

Nikki Coble |

Lady Bracknell |

Jill Tanner |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Algernon |

James Knight |

Chasuble |

Tim True |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gwendolen |

Kate MacCluggage |

Lane/Merriman |

Todd Van Voris |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Miss Prism |

Sharonlee McLean |

Jack |

Matthew Waterson |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

*For an interview with Chris Coleman, artistic director of

Portland Center Stage, on Earnest,

the economy, and The Gerding Theatre: http://kboo.fm/node/12360 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

·

Tiffany Perala gained her Ph.D. at The

University of Nottingham and now teaches in the English Department at

Marylhurst University, Portland, OR. She is an Associate Editor of THE OSCHOLARS. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

OTHER REVIEWS OF FIN DE

SIÈCLE INTEREST |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

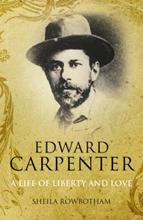

Michael Robertson: Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University

Press, 2008. xiii + 350 pp. ISBN 978 0

691 12 808 5. $27.95. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Disciples in Michael

Robertson’s subtitle are persons who regarded Walt Whitman not simply as a

poet but as a seer or prophet. They

saw Whitman, for instance, as presenting a religious alternative to a

Christianity badly damaged by Darwin. Of one Disciple, R.M. Bucke, Robertson

says, he ‘took the typical Victorian belief in progress and applied it to the

religious realm: human consciousness was evolving and, Walt Whitman was the

latest, best, and most perfect example of a fully evolved spiritual being’

(99). Or they saw in Whitman’s paeans to affection and friendship the basis

of a classless democracy. Or they

found in his frank acceptance of the body a new sexual freedom, heterosexual

or homosexual. Robertson focuses on

nine Disciples, with several others receiving briefer mention. Here, somewhat abridged, are identifications

of six, based on Robertson’s own initial list (xi-xii): William O’Connor

(1832-1889), American author of the influential pamphlet on Whitman ‘The Good

Gray Poet’ (1886); John Burroughs (1837-1921) ‘American nature writer’; Anne

Gilchrist (1825-1885) ‘English writer’; R.M. Bucke (1837-1901) ‘Canadian

psychiatrist,’ author of Cosmic Consciousness (1901); J.W. Wallace

(1853-1926) ‘Leader of the Whitmanite Eagle Street College in Bolton’

England; Horace Trauble ((1858-1919) ‘American writer,’ compiler of the nine

volume With Walt Whitman in Camden.

Robertson’s identifications of the remaining three, John Addington

Symonds, Edward Carpenter, and Oscar Wilde, aren’t required for readers of The

Oscholars. Robertson says he

selected these nine in part because they all, with the exception of Symonds,

met Whitman in person; Symonds is included because he carried on a

correspondence with Whitman for over twenty years. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Robertson reports that Whitman

scholars in the academy usually dismiss the Disciples as fanatics; one of the first serious academic

studies of Whitman dubbed them the ‘hot little prophets’ (279), a title that

has stuck. Robertson defends the

disciples’ mode of responding to Whitman; his Afterword contains interviews

with readers in our time who continue to respond in this mode, even if

they’re more ‘eclectic’ in their sources of spiritual guidance (294). The book argues by example, or better, by

testimony, principally the testimony of the nine. While I’m not a Whitman

scholar, it seems to me Robertson makes his case; as Aristotle observes,

whatever has happened is possible: if Whitman’s writing and Whitman himself

affected so many intelligent persons so profoundly, then this is certainly a

possible response. What’s less clear

to me is what difference, if any, recognizing this response as legitimate

would make to the academic study of Whitman, which I assume is based on the

explication of his works. The

Disciples as represented here don’t seem, even in Robertson’s eyes, to be

particularly careful readers. Of

course, Robertson isn’t asking that the disciples’ mode of response replace

the cooler academic manner, only that the human value of the intense mode be

respected. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It’s not easy to tell what

Robertson’s intended audience is. His

discussion is informed by scholarship, but he isn’t obviously trying to

advance that scholarship. There are end notes gathered at the back of the

book and arranged by page numbers; notes introduced by ‘See’ list books and

articles on persons or topics discussed in the text. In some notes, Robertson indicates a

special debt to an item, but for the most part it’s not apparent how he’s

drawing on or adjusting this commentary.

Some potential readers of the book well acquainted with one or more of

the first six Disciples listed above may be surprised that I thought it

necessary to identify these persons. I

suspect, though I can’t be sure, that those readers’ familiarity with those

figures will mean they won’t find a lot new in Robertson’s discussion. If he does advance the commentary, it’s

probably due to the book’s broad scope.

His end notes indicate that in some cases there already are studies of

the relation between Whitman and particular Disciples. Robertson’s broad survey, however, puts him

in position to compare and contrast the Disciples’ responses to Whitman in a

manner these other studies may not. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Perhaps the best audience are

readers intrigued by Robertson’s subject but not deeply knowledgeable about

it: general readers or academics vacationing as general readers. Robertson typically provides a narrative

of a Disciple’s life, places his or her intellectual concerns in broader

nineteenth century contexts, and glosses the person’s works, especially those

influenced by or about Whitman. This

is all nicely done; Robertson writes clearly, paces his discussion well, and

cites his primary materials effectively throughout. The Disciples’ intense reactions to Whitman

produced remarkable stories. The

English woman Anne Gilchrist, for instance, widowed eight years with four

children, fell in love with Whitman through reading Leaves of Grass,

wrote letters to Whitman proposing marriage, and though Whitman tried to

deter her, put three of her children and her furniture on a steamship in 1876

and came to America. She apparently

knew immediately when she and Whitman met in Philadelphia that there wouldn’t

be any marriage, but she settled near him, and Whitman was a regular visitor

in her house for nearly three years until she returned to England. As Robertson says, she ‘was able to make

the about-face from infatuated would-be lover to friend, hostess, and

disciple with extraordinary facility and grace’ (77). The sense of possibility that the

Disciples found in Whitman led several of them to be active in the social and

political affairs of their timethis activity itself being testimony to the

authenticity of their mode of response.

To put these lives in context, Robertson includes overviews of topics

like nineteenth century spiritualism, the governance of insane asylums, the

Arts & Crafts movement in America, and the difference between European

Marxism and the American socialism of Eugene Debs, among several others. While readers may find some of these

overviews conventional, the breadth of the book is such that they should find

others informative. In fact, readers’

responses to both Robertson’s discussion of persons and topics will fall now

at one point and then at another on a sliding scale from general reader to

specialist: while I’m better acquainted with the British portion of

Robertson’s material than with the American, I wasn’t familiar with Edward

Carpenter’s invention of the category ‘intermediate sex’ (184-8). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Robertson’s treatment of the

figure of most interest to readers of this journal, Wilde, is relatively

brief, occupying the last third of a chapter subtitled ‘Whitman and Same-Sex

Passion,’ which also treats Symonds and Carpenter. The account of Wilde’s first visit in

January 1892 to Whitman in Camden New Jersey is roughly similar to Richard

Ellmann’s (Robertson lists Ellmann’s biography as one source). That visit went very well, and Robertson

makes a shrewd observation about the nature of its success. Each man ‘was able to give the other

exactly what he needed.’ Wilde ‘linked

Whitman, whose verse was considered crude and unartistic by most Americans,

with the European high art tradition.’

Whitman’s praise of Wilde himself linked ‘the young aesthete with

Whitman’s own plainspoken, virile persona’; thus ‘Oscar gave Walt class; Walt

gave him manliness’ (190-1). (In an

end note, Robertson’s acknowledges his debt to Alan Sinfield’s The Wilde

Century for its caution not to impose our notion of a gay identity upon

the period; thus the opposite of ‘manliness’ here is effeminacy rather than

homosexuality.) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Robertson draws this chapter to a

close by claiming that ‘all three English disciples versions of same-sex love

differed fundamentally from Whitman’s’.

Wilde’s version, ‘effeminate, elite, and individualistic’ is taken as

obviously different. ‘Symonds, for

all his talk of the union of sexual inverts across class lines, thought of

sexual behavior as primarily a private matter . . . .’ Carpenter ‘agreed with

Whitman that the love of men for one another could be a positive political

force, an integral part of a more democratic future.’ But Carpenter still believed that persons

had innate sexual proclivities; ‘Whitman, in contrast, was not trying to

differentiate a special category of men . . . he was identifying a capacity

for love that existed in every person. . . .’ (196). While Robertson’s habit

of gathering together the threads of his discussion is a virtue of the book,

the place given Wilde in this comparsion is dubious. That place repeats Robertson’s earlier

claim that ‘Wilde regarded his sexuality as a mark of distinction, one more

way--along with long hair, flamboyant clothing, and witty epigrams--of

setting himself above the philistines’ (195).

Apart from some remarks about The Picture of Dorian Gray as

‘intended to be fully accessible only to a textual and sexual elite,’ (195), it’s

hard to tell why Robertson accepts this simple explanation of a complex

matter. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Given that during Wilde’s first

American visit he did make a point of seeking out Whitman, it’s

understandable that Robertson would include him, but Wilde really doesn’t seem

to have been a Disciple. Reading

Whitman didn’t provoke in Wilde the conversion experience that it did for

some of the other Disciples. Robertson

uses Wilde’s review ‘The Gospel According to Walt Whitman’ (1888) in which

Wilde calls Whitman ‘a factor in the heroic and spiritual evolution of the

human being’ as a sign of Wilde’s ‘interest in a Whitmanesque spirituality’

(194). Wilde, as Robertson notes, does

connect evolution and human progress in ‘The Soul of Man,’ but Wilde’s remark

in the review may only indicate that by this date he’d heard other people

talking about Whitman in this manner too.

In any case, Whitman couldn’t have been that important for Wilde since

what was apparently easy for Whitman was difficult for Wilde. According to Robertson, ‘Whitman’s poetic

self constantly assumes other identities...’ ‘‘Divine am I inside and out,’

Whitman writes, but since I and you are interchangeable, you

are as divine as I’ (19). Wilde did

share Whitman’s personal or subjective perspective, but Wilde also says in a

letter to Robert Ross ‘at the beginning, God made a world for each separate

man’ (1 April 1897). Wilde’s

subjective perspective is more self contained, making contact with other

persons harder; indeed, Wilde sometimes rejects the effort: ‘One should never

listen. To listen is a sign of

disrespect to one’s hearers’ (A Few Maxims for the Instruction of the

Over-Educated). Robertson further

observes that ‘Whitman recognized that, crucial as it was, individuality was

not sufficient. His religious vision

also included empathy, compassion, and love’ (21). Wilde was capable of compassion and love in

life, and these are values endorsed in a work like ‘The Happy Prince’. But again, there’s a tension between

Wilde’s individualism, its self-preoccupation, and the capacity to attend to

other persons. This tension may

underlie one of the many puzzles about The Picture of Dorian Gray. Late in the novel, when Harry says to an

anxious Dorian, ‘You are in some trouble.

Why not tell me what it is? You

know I would help you,’ Harry’s concern for Dorian seems entirely genuine (Complete

Works, 3, 342). But this is the

same Harry who delights in his influence over Dorian, even though ‘to

influence a person is to give him one’s own soul’ (Complete Works, 3,

20). The puzzle is how to reconcile

Harry’s concern with Dorian’s welfare with his desire to make Dorian an

extension of himself. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Robertson’s book certainly

shouldn’t be judged by its treatment of Wilde, nor, I suspect, primarily by

its contribution to the scholarship on any particular Disciple. At times Robertson seems somewhat defensive

about persons who read for spiritual enlightenment, but non-academic readers,

to their credit, typically regard literature as, in Arnold’s famous phrase,

‘a criticism of life’. To these

general readers, or academics venturing beyond their specialties, the book

can be recommended for its crisp presentation of an impressively broad range

of knowledge about Whitman’s impact on the nineteenth century. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

·

For a bibliography of Dr

Bashford’s writings on Wilde, click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Esther Rashkin, Unspeakable Secrets and the Psychoanalysis

of Culture. Albany: State

University of New York Press, 2008. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Esther Rashkin's ambitious

collection of essays purports to elaborate ‘a new form of psychoanalytic

cultural studies’–a brilliant goal, one that, in my opinion ought to be

pursued by more critics. She adds,

‘The theme that unites all my readings is the unspeakable secret: the

shameful, conflicted, undigestible drama that so threatens a character's

ability to be that it must be elided from language and either held in an

unassimilated, unintrojected state of suspension, or incorporated and encased

within an intrapsychic vault designed to insure its integrity and prevent its

revelation’(19). What she wants to do

with the secrets discovered is not absolutely clear. The general intent–highly desirable–is to

explore the ways in cultures employ unconscious strategies in order to remain

unaware of their exploitation of other civilizations. The historical situations explored include

France's colonization of Algeria and issues involving Jewish identity and the

Holocaust. In the case of Oscar

Wilde's novel, The Picture of Doran

Gray, psychoanalytic theory is misguidedly applied to the ‘narrative

life’ of the literary character Dorian in order to throw light on England's

exploitation of Ireland. An approach

that does not begin by working with Dorian as a figure springing from the

creativity, the desires, and the conflicts of the man Oscar Wilde will lose

its way in connecting Dorian to Wilde and Wilde's world. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The theme of the ‘unspeakable

secret’ remains a weak thread. Even

though some of Rashkin's insights into character and culture are

illuminating, the definition of ‘unspeakable secret’ remains inconsistent–as

her own adjectives indicate–changing from one essay to the next and sometimes

within the essay. ‘Undigestible’ drama

turns out to work nicely as a metaphor in her essay on Babette's Feast, in which, Rashkin insightfully suggests, Babette

needs to grieve, is prevented from doing so by her conflicts, and seeks in

the preparation of her feast to find a ‘recipe for mourning.’ But Rashkin has not succeeded in

establishing a psychoanalytic theory that is consistent enough to use

meaningfully. ‘Unintrojected’ and

‘intrapsychic vault’ may not really mean the same thing, and the former has

always been a murky concept.

‘Introjection’ is a psychoanalytic term introduced in a 1909 paper by

the Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi, used by him so broadly that it

could hardly be distinguished from projection, though they are quite

different processes. Projection

involves rejecting a thought or feeling by convincing oneself that it is

really part of the outside world.

Freud elaborated on Ferenczi's term in a 1915 paper, ‘Instincts and

Their Vicissitudes,’ linking introjection to infantile fantasies of oral

incorporation, that is, the feeling that ‘I would like to take this person or thing inside

myself, so I'll eat it.’ Babies shove

any and all colorful objects into their mouths, and we all try to take into our

sense of ourselves qualities outside ourselves that we admire. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As I understand Rashkin's

statement, she means that her readings explore a secret remaining silent

because articulation would either establish or increase awareness of a

painful truth that threatens the sense of identity– the identity of an

individual person or that of a culture.

In the first case the secret is repressed in the Freudian sense of

that term; in the second it is not. An important influence on Rashkin's

thinking is Lacan and his views on language, in particular the idea that the

Unconscious is structured like a language, as well his belief that ‘it is

only once it is formulated, named in the presence of the other, that desire

appears in the full sense of the term.’

Both ideas borrow from Freud's concept of repression, but I find them

unclear. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Freud's writings, the theory

of repression, is, as he wrote, in The

History of the Psychoanalytic Movement (1914), the ‘cornerstone on which

the whole structure of psycho-analysis rests,’ and can be approximated as the

operation by which thoughts and feelings connected to strong instincts,

sexuality and aggression, get pushed out of awareness in order to avoid pain

or conflict. One could extend the

concept to a whole culture if each member of that culture is united in a

desire to forget the same thing. In

Rashkin's remarks quoted above, she appears to be suggesting that she expects

to find in each of the works she explores a secret so shameful or disturbing

to an individual person or a culture that it gets confined to a deeply

unconscious part of the mind, or of the cultural memory, which will not be

integrated into the rest of the desired conscious identity. Rashkin prefers alterations of Freud's

concept of repression that she finds in the writings of Nicolas Abraham and

Maria Torok as well as Sándor Ferenczi.

All three were highly creative and original thinkers, but rather

idiosyncratic interpreters of Freudian concepts, who felt limited by certain

issues key to Freudian theory. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rashkin's final chapter, on which

this review will focus, addresses Wilde's novel The Picture of Dorian Gray as a ‘subtle commentary on the British

colonial enterprise, on Wilde's own complex negotiations with Irish

nationalism and Anglo-Irish identity, and on the psychological legacies of

personal and political abuse’ (23).

Rashkin begins with a letter written by Wilde one week after his

two-year prison term had ended. In it,

Wilde distinguishes between a child's ability to comprehend a punishment

inflicted by a parent and its inability to understand one inflicted by

society. Rashkin uses this distinction

to elaborate on themes of child abuse that she finds in Wilde's novel and

interprets as Wilde's expression of punishments inflicted on Ireland by England. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published in the Daily Chronicle of London, the letter

derides the treatment of children in prison.

Calling attention to the prison authority's ignorance of the ‘peculiar

psychology of a child's nature,’ Wilde asserts that ‘a child can understand a

punishment inflicted by an individual, such as a parent or guardian, and bear

it with a certain amount of acquiescence.’ He adds, however: ‘What it cannot

understand is a punishment inflicted by society.’ I believe that what Wilde meant by these

remarks is that children do not apprehend abstractions easily: they think

concretely. Anything that has not been

seen, held, tasted, touched, or heard by a young child will mystify him or

her. When I told my daughter, then age

three, that she was going to fly to New York with me, she asked whether we

had wings. A child knows ‘family’ as

its siblings and caretakers, but it cannot know ‘society’ because it has no

sense impression to correspond with that term. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rashkin, however, asserts that

Wilde's distinction between a child's attitudes toward punishment by a parent

and punishment by society essentially elaborates the same theme she finds in The Picture of Dorian Gray, namely, ‘a

complex saga of child abuse . . . cryptically inscribed within the

narrative.’ (158) She will later connect the idea of an

abusive society to the abuse visited upon the Irish by the English. Her assertion regarding child abuse, within

the novel appears to stand or fall on the validity of regarding Dorian Gray not as a literary creation inseparable

from the creativity and conflicts of Oscar Wilde but as a real person who was

emotionally abused as a child and who has developed conflicts stemming from

this abuse. ‘I want to argue,’ Rashkin

writes, ‘that Wilde's text narrates a tale of emotional abuse and dramatizes

its ramifications for the narrative life of a the main character’ (158). She plans also to expose the novel's

‘unseen connections between abuse and aesthetic creation, and between psychic

oppression and the production of a symptom.’ (158) When the latter aim is fully achieved, one

ends up with something like Edmund Wilson's The Wound and the Bow (1941). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rashkin also wants to reveal ‘a

secret drama of sexual abuse’ that is promised as ‘the key’ to understanding

‘how the story engages with Irish nationalism, British empire, and the

abusive rapport between colonizer and colonized.’ (159) She believes that

Wilde's prison letter about children not understanding a punishment by

society ‘can be read in conjunction

with the novel as a symptom of Wilde's own complex relationship to Irish

identity, British imperialism, and his own family history.’ (159). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I would have expected at least a

glance at Wilde's family history at this point –Rashkin takes another forty

pages to get to his family–since his parents, especially his mother, were

deeply engaged in Irish culture, and his mother considered herself a

revolutionary for the Young Ireland movement.

As is well known, but not pointed out by Rashkin, Wilde's mother wrote

a famous article that resulted in the arrest and trial of her editor, ‘Jacta

Alea Est’ [The Die is Cast] in which she envisions ‘a hundred thousand

muskets glittering brightly in the light of heaven, and the monumental

barricades stretching across each of our noble streets . . .’ (quoted in

Melville, 36-7) She gave her Oscar the

names of heroes from Irish legend and warlike relatives: Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was

his full name. She was proud of

pumping nationalist ideology into her sons;

‘I made them indeed/Speak plain the word COUNTRY’ is the dedication in her book of

poems. (Knox, 7) These specific details, as well as her

Protestant family's disapproval of her involvement with the largely Catholic

Young Ireland movement and her own deep conflict between supporting and

deriding the Irish peasants seems to me the place to start in looking for

Wilde's conflicts about Ireland and England.

Not included in Rashkin's commentary is, for example, Wilde's remark

in a post-prison letter of [?18 February 1898] to Robert Ross that ‘A patriot

put in prison for loving his country loves his country, and a poet put in

prison for loving boys loves boys’ (Complete Letters, 1019). A psychoanalytic interpretation can find

much that is relevant in the connections that Wilde himself makes between his

identity as a gay man and his conflicted wish to be an Irish hero. Culture is a complex thing, and the critic

who approaches the psychoanalysis of culture must, I believe, have a stronger

sense of history, an anthropologist's awareness of approaching a remote

world. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Because Wilde wrote that he had inserted

himself into his novel, it is unfortunate that Rashkin appears to be unaware

of remarks that he made on the subject.

In another letter highly relevant to interpretations of Wilde's novel

that she does not include, postmarked

12 February 1894 to Ralph Payne, Wilde wrote: ‘I am so glad you like that

strange coloured book of mine: it contains much of me in it. Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord

Henry, what the world thinks me: Dorian what I would like to be–in other

ages, perhaps.’ (585, Complete Letters) If Rashkin's assumption of abuse is

correct, what are we to make of Wilde's desire to be Dorian, his wistful

admiration of Dorian's good looks, his introduction of Dorian as ‘a young man

of extraordinary personal beauty,’ not as someone who is being tortured by a

wicked grandfather, one Lord Kelso, who is in the 1891 version of the novel

the grandfather of Dorian Gray. In the

novel, Lord Kelso is described as not wanting his daughter, Margaret

Devereux, to marry the ‘penniless . . . nobody,’ Dorian's father, and so

Kelso, ‘a mean dog’ contrives to get the nobody killed a few months after the

marriage by a ‘Belgian brute who spitted his man like a pigeon’ (31, Complete Works) Rashkin arrives at the theory that Kelso committed

incest with his daughter, Margaret, that he is both Dorian's father and

grandfather, that he hates the boy for being like his mother. In her interpretation the hidden portrait

expresses the sexual abuse of the daughter and the emotional abuse of Dorian. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The main evidence offered for

this is ingenious: ‘Devereux’ and

‘Kelso’ are names associated with worms–Kelso, she believes, ‘behaves like a

worm . . . looks like a worm’ and besides, his name ‘confirms his verminous

identity: Kelso rhymes with Kell + sew

(something that) spins or 'sews' a 'kell' or cocoon’ (178). All this via the O.E.D.

‘Devereux’ is meanwhile associated with the French word ‘véreux,’

which means ‘decayed, vile, rotten, corrupt, shameful . . . or , literally, 'worm-eaten'.’ On to poisons in Dorian Gray, images of old

and worm-eaten decayed flesh covered with jewels, all interpreted as the

‘poison’ of incest, and from that we get ultimately to ‘Wilde's attempt to

construct a hybrid space of Anglo-Irish identity by simultaneously

identifying with the empire subordinating him as Irish and with the colonized

Irish resisting subjugation.’ (195). Of course Wilde identified himself both

with the English empire and the Irish resisters, but do we need child abuse

to discover this?. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Kelso’ rang a bell, so I started

with Google–wondering if I'd find the name of a household cleanser–but it

turns out to be the name of a Scottish border town. Now, Wilde often used place names for

characters–Windermere, Worthing, Bracknell are a few examples–and Kelso is

not just any old town; it's the town, and the region, from which the noble

house of Douglas–yes, as in Bosie Douglas–is said to spring. The first listing on Google explains that

the monks of Kelso granted lands to the Douglas clan sometime between 1175

and 1199. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But of course most scholars think

Wilde hadn't met Bosie Douglas by the time he wrote Dorian Gray. The Lord

Kelso character, however, only appears in the 1891 version, and here is what

Oscar Wilde had to say about when he met Bosie Douglas in his letter to More

Adey of 7 April 1897 (see p. 795): ‘The friendship began in May 1892 by his

brother appealing to me in a very pathetic letter to help him in terrible

trouble with people who were blackmailing him. I hardly knew him at the time. I had known him eighteen months, but had

only seen him four times in that space.’

If Wilde really had known Douglas for eighteen months before 1892,

then it seems possible that the Lord Kelso figure is some sort of private

joke. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Meanwhile, I wrote to Debrett's Peerage–since 1789, a well

known genealogical guide to the British aristocracy–and asked if the name

‘Kelso’ really was the ancestral home of the Douglas clan and what other

meanings could be attached to the term.

I knew that many nineteenth-century novelists who wanted to include

aristocratic names and characters used Debrett's

the way we use Wikipedia; Wilde mentions it in two stories; Sir Arthur Conan

Doyle, George Orwell, and Saki were among those who dipped in for names. Charles Kidd, the Debrett's representative, e-mailed back as follows: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I am

quite surprised that Wilde used Kelso in his 1891 version of Dorian Gray. Mind you, only a peerage-reading fanatic

would have picked up that it was one of the Duke of Roxburghe's subsidiary

titles; an ordinary member of the public almost certainly would not have made

the connection. But it might be

equally fair to surmise that the then Duke was not of a litigious persuasion,

otherwise I think he would have had good grounds to sue. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another Oscar Wilde trial! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If Wilde had met Bosie Douglas before writing

the book version of his novel, then it would make sense for him to have done

more than flip through Debrett's

Peerage at random, looking for names that sounded good. What if Wilde consciously picked a name

that resonated personally? The wicked,

wicked Lord Kelso in the novel certainly is consistent with the ‘mad, bad’

Douglas family, Lord Alfred and his father the Marquess of Queensberry merely

being among the more flamboyant members.

The Marquess, who was known for his rules for boxing, took a swing

whenever the spirit moved him, which was often, and died shouting that he was

being ‘hounded by the Oscar Wilders.’

Bosie, as everyone knows, fired a pistol shot at the ceiling of a

fashionable watering hole when he desired the other patrons to stop

delicately averting their eyes from himself and Wilde. Well, I've written to the current Lord

Queensberry–address kindly provided by Debrett's–to

see what he thinks of all this. If he

writes back, I'll ask if I may send on his insights to THE OSCHOLARS. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I don't reject Rashkin's worm

imagery, incidentally: I think her

linguistic interpretations useful in suggesting yet another reason for Wilde

to have found the names of Kelso and Devereux attractive. The ‘poison’ that Wilde alludes to with his

imagery of decay in The Picture of

Dorian Gray is the likely a real one:

the syphilis named by one of his favorite writers, Joris Karl

Huysmans, the man whose book provided a blueprint for Wilde's novel, the man

whose main characters, Des Esseintes, is obsessed with syphilis. Wilde's belief that he had syphilis–and his

probable infection with it–should enter into any discussion of his sense of

oppression, since any feeling of political or sexual injustice would be

complicated by a regret at having been compromised physically. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A glance at the history of late

Victorian England should alert all writers wading into psychoanalysis or cultural

studies that every family had at least one member who was afflicted with

syphilis, that all available treatments were highly toxic, that symptoms were

entirely unpredictable and that there was no cure. Why presume incest as a ‘poison’ when

there's so much actual poison lying around?

It would be natural for a syphilitic to feel decayed, worm-eaten. The spirochete, the organism causing

syphilis, looks like a worm, but wasn't discovered until 1905. Even so, any physician of Wilde's day who

had done autopsies would likely have had occasion to discover the vermiform

shapes left by the animal as it bored into the bones and the brain, so the

worm imagery was probably around in Wilde's day. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Psychoanalysis of culture begins

at home–with the family of the subject being examined, meaning as thorough a