|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

An Electronic

Journal for the Exchange of Information |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

on Current

Research, Publications and Productions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Concerning |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oscar Wilde and His Worlds |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Issue no 45 : July 2008 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sir Max Beerbohm

(1872-1956), Oscar Wilde. Pencil, ink, and watercolour, [ca.

1894-1900] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

© Estate of Max Beerbohm. Mark Samuels Lasner

Collection, on loan to the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This featured

prominently in the Facing the Late Victorians exhibition, the Grolier Club,

New York, 21st February–26th April

2008. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

EDITORIAL PAGE |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Navigating THE OSCHOLARS |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Since November 2007 we have split this page into two

sections. SECTION I now contains our Editorial, short pieces that we

hope will interest readers and innovations. SECTION II is a Guide or

site-map to what will be found on other pages of THE

OSCHOLARS with explanatory notes and links to those pages

(formerly to be found on the Editorial page). Each section is prefaced

by a Table of Contents with hyper links to the Contents themselves. For

Section I, please read on. |

Clicking clicking clicking

The sunflower |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE OSCHOLARS is

composed in Bookman Old Style, chiefly 10 point. You can adjust the

size by using the text size command in the View menu of your browser. We do not usually publish e-mail addresses

in full but the sign @ will bring up an e-mail

form. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nothing in THE OSCHOLARS © is copyright to the Journal save its name (although it may be to individual contributors) unless indicated by ©, and the usual etiquette of attribution will doubtless be observed. Please feel free to download it, re-format it, print it, store it electronically whole or in part, copy and paste parts of it, and (of course) forward it to colleagues. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As usual, names emboldened in the text are those of subscribers to THE OSCHOLARS, who may be contacted through oscholars@gmail.com. Underlined text in blue can be clicked for navigation. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

I.

NEWS FROM THE EDITOR

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Innovations

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In our last issue we announced that our Editorial team

strengthened by three new appointments.

Patricia Flanagan Behrendt

joined us as American Theatre Editor.

Until her early retirement she was a Professor in the Department of

Theatre Arts at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, specialising in History

and Theory. She is the author of Oscar

Wilde : Eros and Aesthetics (Palgrave Macmillan 1991). Under her guidance we will be expanding not

only our coverage of Wilde and other fin-de-siècle playwrights on the American

stage, but placing this in the context of Wilde and fin-de-siècle studies in

contemporary America. Dr Behrendt took

over this post from Tiffany Perala,

who in future will be putting together a section of THE OSCHOLARS addressed

to and encouraging undergraduate writing on Wilde. In this she will be working in harmony with

Andrew Eastham, who is

investigating the teaching of Wilde and Decadence, and thus developing our

reportage of Wilde on the curriculum into an examination of the pedagogical

issues involved. Dr Eastham was

awarded a doctorate from University of London for a project entitled ‘The

Ideal Stages of Aestheticism’, and is currently a visiting lecturer at Royal

Holloway, London and Brunel University, and has recently taught at King’s and

Goldsmiths Colleges in London.

Additionally, we announced that, in conformity with our wish to improve our coverage of the

visual arts of the fin-de-siècle, we were creating a small team of art

historians, where Isa Bickmann has

been joined by Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch

of the National Gallery in Dublin, and by Sarah Turner, who is finishing her doctorate at the Courtauld

Institute in London; since then this team has been joined by Nicola Gauld of the Fitzwilliam

Museum, Cambridge. This has stimulated

us into gathering the visual arts material – chiefly announcements and

reviews of exhibitions and publications – and gathering them into a new

section called VISIONS. We hope this

will expand with the appointment of further Associate Editors. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We also announced that we had been joined by Valerie Fehlbaum of the University of Geneva and Irena Grubica of the University of Rijeka. Dr Fehlbaum is editing an anthology of essays by other members of our team (we will be announcing more about this in a future issue) and Dr Grubica is our Associate Editor for Illyria, by which apolitical and rather literary conceit we are designating the western Balkans. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We also recorded two losses: Maureen O’Connor and Tina O’Toole found that they were no longer able to reconcile their work with us and their other commitments. Dr O’Connor has been succeeded by Aoife Leahy, who is the current President of the National Association of English Studies, the Southern Ireland affiliate of the European Society for the Study of English. Dr Leahy’s second Letter from Ireland will be found below, followed by her interview with Neil Bartlett. We have now found a successor for Dr O’Toole, so being our plan for a section of THE OSCHOLARS addressed to the New Woman, heralded in a previous issue, is no longer in abeyance. The ‘successor’ is in fact a small team of successors, Jessica Cox of the University of Lampeter, Kathleen Gledhill of the University of Hull, Petra Dierkes-Thrun of the State University of California at Northridge, Christine Huguet of the University of Lillie III – Charles de Gaulle, and Alison Laurie of Victoria University in Wellington. This group is joined by Sophie Geoffroy, editor of The Sibyl, to ensure co-ordination of effort. This means that we have enlarged our ambition, and we will be launching a new journal called THE LATCHKEY in September / October. This will have its own mailing list, and we encourage interested readers to sign up for this. We will be calling for papers later. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other new recruits to our team are Krisztina Lajosi (University of Amsterdam), and Tijana Stasic (University of

Gothenburg) who will be reporting on publications, productions, exhibitions

and scholarly activity in Hungary and Sweden; and Emma Alder (Napier University, Edinburgh) and Julie-Ann Robson (University of

Sydney), who succeed Michèle

Mendelssohn as Scotland Editor and Angela

Kingston as Australia Editor, who are too heavily committed

elsewhere. To these are added Naomi Wood (Kansas State University)

who will be editing a special supplement on Oscar Wilde and Children’s

Literature for late Spring, 2009; Carmen

Casaliggi (University of Limerick), who will be assisting Anuradha Chatterjee with our journal

of Ruskin Studies, THE EIGHTH LAMP; and, last but certainly not least, Annabel Rutherford (York University,

Toronto), who becomes our Dance Editor. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This issue of THE OSCHOLARS announces the creation of two new rubrics. ‘Dandies, Dress and Fashion’ will be compiled for us by Elizabeth McCollum, whose opening statement we publish below, and Melmoth, edited by Sondeep Kandola, which will cover the Gothic aspects of the fin-de-siècle. Melmoth can be found at the very end of this page. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Work continues on the reconstruction of the website, with improvements in accessibility and design, so that it becomes a fully-searchable and easily navigated resource. This involves less scrolling and more clicking, enabling us decrease the length of pages. Various pages have been split up, and new ones created. This is largely the inspiration (and wholly the hard work) of our webmaster, Steven Halliwell. VISIONS is one result of this; another is THE EIGHTH LAMP: Ruskin Studies To-day, under the energetic editorship of Anuradha Chatterjee. A third manifestation is the folder of webpages devoted to the Oxford Conference on ‘The Reception of Oscar Wilde in Europe’, which took place at Trinity College on 8th/9th March. These pages will be kept up and expanded, collaborating on-line with Stefano-Maria Evangelista, who is editing the book for which the Conference was the advance guard. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Our special supplement on Teleny, to be published in Autumn 2008, is on course. This is being guest edited by Professor John McRae of the University of Nottingham, whose edition of Teleny was the first scholarly unexpurgated one published. Readers who would like to submit an article discussing any aspect of Teleny should contact Professor McRae @. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

So many chances and changes have necessitated constant revisions

in our publishing schedules, with ONLY RUE DES BEAUX ARTS under Danielle Guérin’s editorship

maintaining its intended two-monthly appearance on time, although after a

shaky start to the year THE OSCHOLARS seems back on track. This has been balanced by our publishing

new content on our website nearly every day, and announcing this in weekly

reports on our ‘yahoo’ subsidiary. The

number of our readers who have joined this has been growing, and it will be

increasingly our medium for making announcements in the place of mass

mailings, which increasingly fall foul of anti-spam traps either at the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

II.

THE OSCHOLARS LIBRARY

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

III.

FREQUENTING THE SOCIETY OF THE AGED AND

WELL-INFORMED: NEWS, NOTES, QUERIES.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cigarettes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Robert Sherard writes that when he was living in Wilde’s

flat in London he smoked Parascho cigarettes.

Does anyone have any information on these (the internet offering no

help)? The reference is Robert H.

Sherard: Oscar Wilde, the Story of an

Unhappy Friendship. London:

Greening & Co. 1905. Popular

edition 1908 p.90. We have discovered

what must be one of the earliest examples of Wilde inspired merchandise: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oscar Wilde and Gemstones

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We are not sure if this subject has been studied,

and would like to hear if it has. Hans-Christian Oeser sends this note: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I searched for alchemy and gems

and male properties, and found the opposition vir rubeus/mulier candida as in

the following (which is sort of applicable to The Young King I would think: redness/whiteness, heavenly

coronation etc.): |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See Jung, Mysterium Coniunctionis, p. 5, n. 4: ‘Senior says: “I joined the

two luminaries in marriage and it became as water having two lights’ (De chemia, p. 15 f.),” and p. 4: “The

opposites and their symbols are so common in the texts that it is superfluous

to cite evidence from the sources ... Very often the masculine-feminine

opposition is personified as King and Queen ... or as servus (slave) or vir

rubeus (red man) and mulier candida (white woman); in the “Visio Arislei”

they appear as ... the King’s son and daughter.’ In a footnote, Jung adds:

“The archetype of the heavenly marriage plays a great role here.’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Vir rubeus, virile ruby - same thing, n'est-ce pas? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And then I found this about male rubies (in German): |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Bezogen auf die Farbe, kann

man bei den Rubinen auch eine Unterscheidung in männliche oder weibliche

finden. Zum Beispiel werden die

dunkelroten Rubine dem Mann und die hell-rosaroten der Frau zugeordnet.’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And lo and behold, A Florentine Tragedy in French: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Un rubis viril enflamme l’agrafe, comme un charbon ardent. Le

Saint-Père n’a pas de telle pierre, Et les Indes ne pourraient lui trouver de

frère. La boucle elle-même est d’un

grand art. Cellini, jamais, ne créa plus belle chose pour le délice’ etc. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This seems to offer a way into the subject, and we would be very willing to consider for publication a developed article. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

J F McArdle |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hilary Wilson is researching 19th century theatre and performance in Sheffield for a University of Sheffield Ph.D. She writes ‘One amusing reference/link with Wilde that I have found so far is in a comedy called 'Flint and Steel' by J F McArdle (1881). A devotee of the 'aesthetes' is made rather a figure of fun, and ends up being locked in a china cupboard...’ We hope it was a blue china cupboard. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

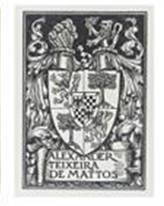

Alexander Teixeira de Mattos |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alexander Teixeira de Mattos (‘Tex’; 1865-1921) married

the widow of Willie Wilde and deserves more than that particular tag. We will return to him in future: here we

have taken the opportunity to download and reproduce his bookplate. As his

name is sometimes given as ‘Texeira’, we can see his preferred spelling. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

‘Passion’s Discipline’

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This was the title of an exhibition held 2nd May to 2nd

August 2003 at the New York Public Library.

Oscar Wilde was represented by a number of items drawn from the Berg

Collection at the Library. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1.

Photograph of Wilde by Napoleon Sarony, signed

by Sarony. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2.

Oscar Wilde: ‘Lotus Land’, autograph MS signed

O.F.O’F.W.W. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

3.

Oscar Wilde: ‘Impression du Voyage’, autograph

MS, unsigned ca.1880. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

4.

Oscar Wilde: ‘Quantum Mutata’ and ‘Libertatis

Sacra Fames’, pages displayed in the edition Poems, London: David Bogue 1881. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5.

Oscar Wilde: ‘E Tenebris’, page displayed in

the edition Poems, London: Elkin

mathe3ws and John Lane 1892. No. 135

of 220 copies printed and signed by the author. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

6.

Oscar Wilde: ‘Ave Maria Plena Gratia’. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is from a collection of pieces by Wilde copied out in a

hand-written anthology by the Belfast author Forest Reid in 1903. This anthology has a cover drawing in the

manner of Beardsley, thought to be by Reid.

Isaac Gewirtz, curator of the Berg Collection, is keen to hear from

anyone working on Forest Reid who may have information on his interest in

Wilde. We note that Reid did write a

novel called The Bracknels. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Picture of Dorian Gray |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Picture of Dorian Gray was broadcast in two episodes on the wireless station BBC7 on Wednesday 2nd and Thursday 3rd July 2008. The novel was adapted by Nick McCarty and the leading parts were played by Ian McDiarmid and Jamie Glover. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Work in Progress

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In December 2006 we published a list of fin-de-siècle

doctoral theses being undertaken at Birkbeck College, University of London,

and a similar list in December 2007. We should very much like to hear

from readers at other universities with news of similar theses they are

supervising or undertaking. We welcome all news of research being

undertaken on any aspect of the fin de siècle. There is a list of dissertations on Irish

literature held on the Princess Grace Irish Library website (http://www.pgil-eirdata.org/html/pgil_gazette/disserts/a/)

but it seems to be impossible to gain access. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jason Boyd

(University of Toronto) has kindly sent us an abstract and bibliography of

his work on Oscar Wilde and Victorian

Edutainment: Lecture Tours as 19th-Century Itinerant Entertainment, and

we are publishing this in ‘And I? May I Say Nothing?’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Wilde Collection

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There is no universal handbook or vade mecum to the

various Wilde Collections, and we have made a start here. Sometimes

where a collection’s contents are published in detail on-line we will simply

give an URL; or we may be able to give more details ourselves. We will

then to be able to bring these together as a new Appendix. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IV.

OSCAR WILDE

: THE POETIC LEGACY

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

“Wilde Tribute Poem – Prison Number C.3.3.” In Reading gaol there is no bail Nor freedom of any chance Just the smell, of a living hell And a warder there to glance With no one there no joy to share Mad spirits come to prance On a poor old soul, locked in a hole And dies in Paris, France From bleak cell walls, where madness falls And drips to a cell floor A playwright who was once so great Is locked behind a door His mind is chained, with hands refrained Not writing anymore A brain is now a prisoner Torturous thoughts of what’s in store In Reading gaol there is no bail Nor freedom of any chance You do your time whatever your crime Appeals get but a glance For C.3.3. it’s sad to see A man so great destroyed Alas! your fate cannot be changed Your genial works enjoyed (Read after poem) C.3.3. Oscar Wilde’s Prison Number, Block C, Floor 3, Cell 3. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

V.

Wilde on the Curriculum : Teaching Wilde, Aestheticism

and Decadence.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We are always anxious to publicise the teaching of Wilde

at both second and third level, and welcome news of Wilde on curricula.

Similarly, news of the other subjects on whom we are publishing (Whistler,

Shaw, Ruskin, George Moore and Vernon Lee) is also welcome. Andrew

Eastham is developing a study of the teaching of Wilde, which we hope

will be helpful to others who have Wilde on their courses; in tandem Tiffany Perala is looking at

undergraduate response. Here Andrew

Eastham presents his introductory declaration of aims and objects: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This

new strand of THE OSCHOLARS provides a space for academics, teachers and

students to reflect on the ways that Wilde, Aestheticism and Decadence are

being taught and disseminated. We will be sharing resources, providing an

overview of courses and methods, sharing our experience as teachers and

imagining new ways of reanimating the fin de siècle in the classroom.

Although the main focus will be on departments of English in Europe and North

America, we are interested in hearing from scholars worldwide about their

practice. In some postings we will focus on the teaching of specific texts by

Wilde and others, in others we will take a larger focus on issues such as the

teaching of performance in Aesthetic culture, the relative roles of cultural

history and textual scholarship, teaching Wilde and sexuality, or teaching

Aestheticism as a movement. In the opening discussions I will introduce some

of the broader decisions involved in teaching Aestheticism and Decadence and

assess current academic trends on the following questions. How do we

construct courses on Aestheticism and Decadence historically and conceptually?

Can we provide an adequate focus on the multiple issues of contemporary

scholarship – cultural history,

theoretical aesthetics and sexual identity politics – within an introductory course? Do we

teach Wilde as theory, literature, or drama? Are Pater’s model of the

‘aesthetic critic’ and Wilde’s ideal of the ‘Critic as Artist’ still alive in

the classroom today? How do we encompass the breadth of artistic media

embraced by Ruskin, Pater, Wilde or Lee in the classroom? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It’s

reasonable to assume that any teacher working in this area has at some point

had to temporarily forge an intellectual identity well outside the confines

of their research: it is arguably simply not enough to be a literary scholar

to teach Aestheticism and Decadence, and we may have to temporarily don the

mask of the critic of painting, architecture, music or dance. In true Wildean

fashion, though, these forgeries might well lead to vital areas of our

research and the most felicitous subjects for the classroom. In personal

experience, being forced to dissimulate a speciality in fin de siècle visual

culture to a mixed group of Fine Art and Literature students opened my eyes

to relations between image, text and music that I’d hitherto addressed only

in theory. In cases like this, a pact emerges – if the students are

implicitly aware that we are learning on the job, we hope for their

generosity in allowing for a shared discovery. This kind of experience is

integral to an area where we cannot hope to master all contexts, especially

since British Aestheticism and Decadence incorporates such a vast array of

European literary and artistic reference. Furthermore, the theoretical

sources of Pater, Wilde or Symonds’s work are vast, encompassing Kant,

Schiller, Fichte and Hegel, British Empiricism, Spencer’s Sociology and the

Natural Sciences. And even if we consider ourselves master of these

intellectual traditions, another scholar will claim that late Victorian

periodicals should be our primary resource. Any teacher thus faces a choice;

do we limit the archive to a space where the teacher retains a safe grasp on

academic authority, or do we open our study beyond the borders of our

knowledge – allow for a sea of textual echoes that we will never quite have

control over? Then there is the choice of just how much weight we give to the

intellectual contexts of Late Victorian Aestheticism when they are wielded so

provocatively by a figure like Wilde? Should we train students to use the

voluminous and hugely influential theoretical architectures of Hegel’s

Aesthetics or Spencer’s Sociology, or do we risk the accusation of a certain

earnestness which goes too far against the spirit of Wilde himself? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These

personal choices are very clearly connected to broader academic debates, and

the study of the Victorian fin de siècle encapsulates many of the most

pressing issues of modern scholarship and pedagogy. The recently fashionable

demand for ‘Interdisciplinarity’ has always been a necessary and vital

condition of fin de siècle scholarship, and Wilde provides an extraordinary

example of intellectual and cultural border crossings. Furthermore, If

historicism has been ascendant in Victorian literary studies for over a

decade now, then Wilde’s work offers both an argument for such practice, in

his own dissertation on ‘The Rise of Historical Criticism’, and an ideal

space to question such orthodoxies, in the brilliant play with historical

scholarship and forgery of ‘The Portrait of Mr W.H.’. The latter work, along

with his dialogues ‘The Critic as Artist’ and ‘The Decay of Lying’, suggest

the kind of challenge that Wilde offers to contemporary teachers of

literature. When faced with such dazzling examples of scholarly innovation,

how can we live up to Wilde, both in style and breadth of thought? Can we

respond to this challenge within the dominant pedagogic model of historical

periodization, or do Wilde and Aestheticism call for new teaching methods

that incorporate creative writing or experimental critical forms? One of the

ways of asking this question will be to allow teachers from different

academic disciplines to challenge each other’s practice. Of all academic

disciplines based on creative practice, English literature has effected the

most radical divorce between criticism and practice. The significant growth in

creative writing across English Departments in Britain and America may change

this, but what kinds of dialogue can we envisage between the critical and

creative wings of the academy? The differences in the way that literature and

drama are taught will be one of the most important ways that we will address

this question; the question is central to the teaching of Wilde, and the

Oscholars has always been a vital format for tracing dramatic and critical

practice together. But equally, the declining role of theory in the classroom

needs to be a central issue. Pater and Wilde were innovative theorists who

were writing during the emergence of academic literary studies – Pater was

ambiguously positioned within the academy and Wilde within the growing

apparatus of consumer culture. Critics like Regenia Gagnier, Ian Small and

Jonathan Freedman have used these ambiguous positions as the means to reflect

on the conditions of professional criticism and the role of art in society.

Our aim here is to continue these kinds of debates around teaching practice.

I’ll begin by introducing a year long MA course on ‘Aestheticism and

Decadence’ which I taught recently and discussing some of the decisions and

problems this involved, before going on to canvass the opinions of a wide variety

of scholars. We’d be very grateful to any teachers and students who want to

offers their opinions and send us links to their resources; our purpose is to

broaden the teaching community as well as provide a space for thought. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contact THE OSCHOLARS at oscholars@gmail.com or Andrew Eastham

at @. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here is the list of prescribed texts for the Irish Leaving Certificate Examination in English, 2008. ‘As the syllabus indicates, students are required to study from this list: One text on its own from the following texts: -‘BRONTË, Emily: Wuthering Heights; ISHIGURO, Kazuo: The Remains of the Day; JOHNSTON, Jennifer: How Many Miles to Babylon?; Mc CABE, Eugene: Death and Nightingales; MILLER, Arthur: The Crucible; MOORE, Brian: Lies of Silence; O’CASEY, Sean: The Plough and the Stars; SHAKESPEARE, William: Othello; WILDE, Oscar: The Importance of Being Earnest. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Florina Tufescu (Dalarna University) sends us the following: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wilde courses: Undergraduate: ‘Major Authors: Oscar

Wilde and the 90s’. Spring 2003 Prof. Stephen Tapscott. Syllabus, assignments

and additional resources from Massachusetts Institute of Technology

OpenCourseWare |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Importance of

Being Earnest – As A-level, EFL module at the Swedish School in

Fuengirola, Spain 2000 FT – As undergraduate seminar on ‘Past and Present’

course at the University of Exeter 2005 FT – As postgraduate seminar on the

‘Ireland in Film and Drama’ course at Dalarna University, Sweden

2006–including clips from the 1988 BBC production–was taught again on 14th

March 2008–course materials and student responses accessible via www.du.se

(open access). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

De Profundis and The Ballad of Reading Gaol

Postgraduate seminar at Dalarna University that also included Banville’s Book

of Evidence 2007 FT |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lady Windermere’s Fan Teaching ideas supplied by Andrew Maunder (University of Hertfordshire)

on the English Subject Centre website http://www.english.heacademy.ac.uk/explore/resources/t3/curriculum.php?topic=10 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Oscar Wilde Society of America and the Indiana State

University Honors Program held an Oscar

Wilde Symposium on 31st March 2008, Indiana State University Terre Haute,

Indiana, featuring presentation of new American Wilde scholarship by Indiana

State University honors students and a keynote address by Dr Joan

Navarre. This event was free and open

to the public. For more information

contact Marilyn Bisch, @ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following is copied from the invaluable VICTORIA RESEARCH WEB: Teaching Resources |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Few things are more

helpful in planning a course than seeing how others have laid out similar

courses. Sharing syllabi is one of the most fruitful uses of the Web, and a

number of Victorianists have made course plans available online for the

benefit of both students and colleagues. If you would like to contribute a

syllabus for posting here, either as a link to a website or as a text file,

please contact the webmaster. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A variety of

additional materials, many of which are especially suited for use by primary

and secondary school teachers, can be found below under Other Teaching Resources. Again,

if you'd like to contribute additional materials like these we'd be glad to

have them. A handy place to search the Web for syllabi on particular topics

is the Syllabus Finder at the Center for History and New Media. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

VI.

THE CRITIC AS CRITIC

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Last issue’s review

section contained reviews by Maria Kasia Greenwood on Leslie Clack’s Oscar Wilde in

Paris, Elżbieta Baraniecka on Oscar Wilde’s Bunbury in Augsburg, María DeGuzmán on Junot Díaz on Oscar

Wao, Elisa Bizzotto on Michael Kaylor on Oscar Wilde, Pater

and Hopkins, Liberato Santoro-Brienza on Elisa Bizzotto on Imaginary Portraits, Laurence Talairach-Vielmas on Andrew

Mangham on Violent Women, Susan Cahill on Laurence Tailarach-Vielmas on women’s bodies, Laurence Talairach-Vielmas on Ann

Stiles on neuorology, Michael

Patrick Gillespie on Madeleine Humphreys on Edward Martyn, Chantal

Beauvalot on Georges-Paul Collet on Jacques-Emile Blanche, Linda

Zatlin on Rodney Engen on Aubrey Beardsley, D.C. Rose on Alexandra

Warwick on Oscar Wilde. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current reviews are Ann M. Bogle on Thomas Kilroy on Constance Wilde; Richard Fantina on Adrian Wisnicki on Conspiracy; Tina

Gray on Joy Melville on Ellen

Terry; Christine Huguet on

divers hands on Michael Field; Yvonne Ivory on Lucia Krämer on Oscar Wilde; Sondeep Kandola on Corin

Redgrave on Oscar Wilde; Ruth Kinna on Brian Morris on Peter

Kropotkin; Mireille Naturel

on Evelyne Bloch-Dano on Jeanne Proust; Maureen

O’Connor on Jarlath Killeen on

Oscar Wilde; Gwen Orel on the

Pearl Company on Earnest; Virginie Pouzet-Duzer on Rhonda Garelick on Loïe Fuller. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Clicking |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

VII. DANDIES, DRESS AND FASHION |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Editor for this section: Elizabeth McCollum |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A new section is debuting

in this issue of THE OSCHOLARS, examining the fashion – and anti-fashion – of

the Fin de Siècle period, especially as it pertains to Oscar Wilde’s works

and philosophy. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I hope to bring you reviews

of many of the recent and current books on the subject of late 19th century

clothing, as well as scholarly papers on both fashion and anti-fashion, the

latter especially as put forward by both the proponents of dress reform and

the artistic and Bohemian communities.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oscar himself was much in

favour of dress reform, and his wife Constance, through his influence

initially, was a vocal member of the Rational Dress Society, and wrote

several articles on the subject. Many

other thinkers and artists of the day championed this new style of dress,

even as it was vilified in such magazines as Punch, and deplored by

fashionable society. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I will also hope to gather,

where possible, reviews and articles on pertinent exhibitions of costume as I

am made aware of them – and assuming that I can either attend them myself or

delegate it to someone in that area. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A LIST OF

RECOMMENDED SITES FOR |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE STUDY OF

VICTORIAN FASHION AND ANTI-FASHION |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

During the course of my own research into Victorian

costume, first for my thesis and now just for the love of it, I have run

across many useful and informative sites, and some rather less helpful

ones. So I thought I would make a list

of those sites that I have come across, so far, that have been of the best

use to me and which I feel I can recommend to other scholars of Victorian

fashion and anti-fashion, and of Victorian history and literature in

general. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A site which sells vintage clothing, including Victorian

and Edwardian pieces. I have not

ordered from them, so I don’t know how reliable or legitimate their pieces

might be. But if nothing else, it does

show the range of Victorian clothing that is out there for sale. Also many of the pieces are displayed in multiple

pictures, depicting their construction and ornamental details, which is an

aid to those who are studying actual costume construction. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A wonderful online collection of images from a collection

put together by the costume historian and designer Blanche Payne, a professor

at the University of Washington. The

fashion plates in the collection cover the period from 1806-1915, and are

both in color and black and white.

Absolutely invaluable for scholars wishing to know exactly what the

latest fashions for these years would be. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ms. Andrews’ site sells antique costumes and textiles, and

again I cannot vouch for the site, but the photos of her objects for sale are

beautiful and, in some cases, quite detailed and enlargeable, which make

them, again, a wonderful source for researchers. Her pieces are quite beautiful and I would

recommend going there simply for the sheer aesthetic appreciation that the

site affords. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One of the few actual exhibitions that has been done on

this subject. Sadly I did not see it

in person, but the online exhibition is just as good. The exhibition covers both the Victorian

fashion that the reformers were seeking to transform and the resulting garments

and undergarments. From one of their

photos of a reform corset, a very talented seamstress friend of mine managed

to create a wearable reproduction of it for my thesis project. A wonderful online resource of both

information and images about this important 19th century movement, so dear to

the hearts of Oscar Wilde and Walter Crane, etc. There are also examples of artistic dress

from England and Europe as well as from America. A site well worth spending some time

reading and examining. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

http://www.loyno.edu/~history/journal/1989-0/rodrigues.htm#46 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

An interesting online article on ‘Rational Dress’ vs.

fashionable dress and the attitudes of both feminists and anti-feminists to

both styles of dress. The article does

not mention artistic dress, confining itself mostly to the ‘ugly’ bloomers

and woolen undergarments and reform corsets contrasted with the restricting

corsets and bustles of the fashionable ladies. The historical background that Ms.

Rodrigues gives is informative and well-footnoted. There are no illustrations to the article,

which is a tiny drawback for those unfamiliar with some of the reform

garments mentioned, but the text strives to describe the costumes in enough

detail to give an adequate idea of the clothing. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

An excellent online seminar in five sessions on the

development of the corset and the crinoline in the 19th and 20th

centuries. Two eminent costume

historians, Suzanne Lussier and Lucy Johnston, take the reader through from

the beginning of Victoria’s reign through to the age of Vivienne Westwood and

Jean-Paul Gaultier. They are very

sensible in their approach to the subject matter, debunking many of the

horror-stories, while not denying that there were some misuses of the

garments that led to the stories in the first place. Well-illustrated and very informative. They do not dwell much on the reform

movements or garments, preferring to concentrate on the fashionable garments

which they had more access to at the Victoria and Albert museum costume

collection, of which Ms. Johnston is a curator. All in all, I recommend this as a precise

and well-written introduction to the subject. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘The Victorian Era Online’. This is rather a catch-all site for a

number of different Victorian subjects, but they do have a whole page of

links on Victorian fashion, some useful, some not. Still, a fun site to poke around on. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And to finish, a couple of recommendations for general

costume sites: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A large site mostly of links to other sites, but an

excellent compilation of resources for all periods of costume. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tara McGinnes’ excellent and immensely copious collection

of links and pages on all manner of costumes, and on design and construction,

as well as purchasing and patterns.

This is my main source of costume knowledge on the net. She updates the site fairly regularly and

most of the links work. There is a

page for every period of history you can think of, and every nation. Some pages are more comprehensive than

others, but she does her best, either with links or articles or images. My only tiny problem with the site is that

it’s a little too busy, too many ads and images on sidebars to distract from

what you’re trying to find. But that’s

a small price to pay for such a fabulous reference site. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

So that is my list, to this date. I’m sure I have missed out on many

wonderful sites, and if indeed anyone has sites to recommend to me, I would

love to hear about them. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Meanwhile, I encourage you to visit the sites I mentioned

above and hopefully, I will be able to post another list in the future with

still more sites. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

VIII.

OSCAR WILDE AND THE KINEMATOGRAPH

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oliver Parker is due to begin filming of The Picture of Dorian Gray at the end

of this month, July 2008. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Posters |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This month’s posters were found for us by Danielle

Guérin. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Trader Faulkner:

Peter Finch – A Biography.

London: Angus & Robertson 1979 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

p.209] ‘In April 1960 work began

on Oscar Wilde. Yvonne Mitchell, who

played Oscar’s wife . . . remembers the sudden change in Peter as the part

took him over. “On the first two days

of filming there was this acquaintance I had known for a number of years as

Peter Finch. On the third day, there

arrived a man I didn’t know, with heavy eye-lids, and a droopy sort of face,

who was Oscar Wilde, and he remained Oscar Wilde from then onwards. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘“Apparently, he used to

sit on Yolande’s bed at night, reading poetry and weeping. He turned into a totally different man...” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Oscar Wilde was an

extremely difficult part to cast because the producers had to find a star of

reasonable magnitude as a box office draw, who could look graceful and

æsthetic, but not overtly effeminate or camp.

Wilde had a beautiful voice and, according to those who remembered him,

had the manner and presence of a theatrical actor of his time . . . |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Ken Hughes and Peter

Finch, as director and star . . . would be a most unlikely choice unless you

knew the capabilities of both men.

Hughes, a voluble Cockney, and Finchie took to one another like the

Corsican Brothers. Ken Hughes is

lucid, intuitive, a marvellous writer with absolutely no intellectual

pretensions. “Finchie and I were on

the same non-intellectualising vibe,” said Ken Hughes. “What I felt about Finch was that he would

level out any suggestion of the camp faggot because he was basically

heterosexual. We do know that Wilde

was poetic, a man of great sensitivity, but I must say Finchie surprised

me. His performance was more

thoughtful, delicate and considered and more Wildean than I ever felt Finchie

was capable of producing.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘As for the swollen hands

Peter seemed to acquire during filming, Ken Hughes felt they were not caused

by the power of thought but by copious bottles of champagne and a surfeit of

potatoes . . . He was becoming visibly more bloated in appearance as time

went on. “Peter did all he could to

get under the skin of his role. He’d

wear his Victorian suit around the house to gllen cast the film. “The ’phone rang. It was Irving to know if I could leave the

typewriter for an hour to go round and meet Peter Finch. I sat opposite Finch, who was absolutely

charming, but I thought, this Finchie Aussie bushranger to play Oscar

Wilde? No way, I thought, who’s

kidding whom? But as far as Irving was

concerned it was a fait accompli. He

had made up his mind. He had the

marvellous native tough Hollywood cunning of the 1940s. Morley on the Goldstein film was probably

closer in appearance and a much more obvious choice for the rôle than Finch,

added to which Morley had already played Wilde in the theatre. I feel that we were lucky in that the

chemistry by a fluke was right with Finch, and with John Fraser as

Bosie. It just seemed to work, and you

can’t analyse that process. We shot in

colour, which helped.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

p.211] ‘Finch, as Wilde,

turned out to be one of the subtlest decisions any casting producer could

have made. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘With both Oscar Wilde

films shooting in the studios, the producers were racing to beat the clock to

the finishing post to be the first out for distribution. Warwick Films, with Peter as their golden

hope, had four spies on the other picture, four crowd extras who were on the

other film but in Warwick’s pay. These

four were picking up two pay cheques, one from Robert Goldstein and one from

Irving Allen. They’d report to Peter’s

studio as soon as they could get from one studio to the other in a fast car,

bringing copies of schedules and daily papers. Peter told a hilarious story about

Goldstein having hell’s own job getting hansom cabs of the period. Finchie’s company hired ever hansom in the

country, parked them out on the Elstree lot and left them there. They just sat there during the whole

picture and never moved. Hughes told

me they also gave Goldstein trouble over costumiers. “Our deal with the London costumiers,

Berman’s, was that they did not deal with Goldstein. We went to Nathan’s, the other London

theatrical costumiers and set up the same deal. The opposition finally wound up advertising

in The Stage with an ad, something like “Wanted, crowd artists with costumes,

two guineas a day”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘From the day they started

shooting The Trials of Oscar Wilde, to the end of the sixth week, they had a

married print with the music score on it, as Ron Goodwin was actually writing

the music for scenes they hadn’t even shot.

He would go to Ken Hughes’ home each evening and Hughes would act out

the scene as it would subsequently be shot.

Goodwin would time it with a stop watch and then off he’d go and write

the music. Next day Hughes would shoot

the scene. It would be a few feet out

here and there, but it was eventually happily “wangled” for the final

print. I asked Hughes if he thought

the film had artistic merit. “an

artistic film? Balls! By the last day of shooting it was like the

last fifteen minutes of the Grand National.

We had to strike a set, union rules went buggery. Pandemonium broke out. The entire unit moved like people in a bomb

scare . . “‘ [There is more of this not very interesting anecdote.] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IX.

LETTER FROM IRELAND

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aoife Leahy

sends us this budget of news. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greetings from Ireland to all the Oscholars. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oscar Wilde was a common thread in the Fifth Annual

International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival’s Cultural/Educational Seminar in

TCD on the 11th May. Dr Colum O’ Cleirigh (St Patrick’s College Drumcondra)

spoke about Aiden Rogers, Prof Roy Sargeant (Artscape, Cape Town) gave a talk

on Mary Renault and Sonja Tiernan (National Library of Ireland) discussed her

research on Eva Gore-Booth. Wilde’s life and work had affected all of these

figures - sometimes as an inspiration, sometimes as a cautionary tale. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dr

Eibhear Walshe (UCC), who also chaired the Cultural

Event, gave a talk entitled ‘Wilde and the New Ireland’ focusing on how Wilde

was perceived by Irish and Anglo-Irish people in the 1930s-1950s. Dr Walshe

spoke about his forthcoming book Oscar

Wilde and Ireland, in which he examines conflicting views of Wilde in

Ireland over a much broader span of time. It will be of great interest to the

Oscholars. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There were also short talks on diversity in the arts by

Brian Merriman and Nick White. As Artistic Director of the festival, Brian

Merriman joined in the questions and answers at the end and contributed some

interesting observations of his own on Wilde’s Irishness and attraction to

Catholicism. He also commented that the festival’s poster and internet

campaign depicting Wilde with a green carnation in his mouth had been a hit. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Theatre Festival was a great success and

the plays on offer were very well attended. At the short plays programme

‘Short Shorts and Very Shorts’ on a sunny Friday evening, for example, extra

chairs had to be brought into the lovely Georgian setting of The Cobalt Café

so that nobody was sent away disappointed.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Wilde – The Restaurant’ recently opened in

The Westbury Hotel, Grafton Street. Since there are various restaurants named

after Wilde all over the world (there is one in Brisbane, Australia, for

instance), it seems appropriate to have one in the heart of Dublin. Meals are

created by chef John Wood and the restaurant is open for breakfast, lunch and

dinner. The restaurant serves locally sourced, in-season produce. The full

menu can be found by clicking the logo.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Wilde – The Restaurant’ recently opened in

The Westbury Hotel, Grafton Street. Since there are various restaurants named

after Wilde all over the world (there is one in Brisbane, Australia, for

instance), it seems appropriate to have one in the heart of Dublin. Meals are

created by chef John Wood and the restaurant is open for breakfast, lunch and

dinner. The restaurant serves locally sourced, in-season produce. The full

menu can be found by clicking the logo.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dublin poet Pat Shortall was so pleased to be mentioned

on Oscholars in May that he has kindly agreed to reproduce the full text of

his poem ‘Wilde Tribute Poem – Prison Number C.3.3.’ for us. Shortall’s recently released collection Bramble

Lane is available on CD (ring 087-2393062 to order), but this written

version with the poet’s own punctuation and layout of the ‘Wilde Tribute

Poem’ is exclusive to the Oscholars. Deliberately unglamorous and down to earth

phrases like ‘you do your time’ and ‘there is no bail’ convey the sense of

sympathy and solidarity that today’s Dubliners have for the ‘poor old soul’

Wilde. (See above). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In an inventive marketing move, The Abbey Theatre has

included Neil Bartlett’s forthcoming production of Wilde’s An Ideal Husband as part of its

‘Season of Love.’ An Ideal Husband

itself will run from 14th August to 27th September, with previews on the 11th,

12th and 13th of August. Other plays in the season include Brian

Friel’s adaptation of Chekhov’s Three

Sisters. There is a discount for booking tickets in advance for three

or four of the ‘Season of Love’ plays. Details can be found on www.abbeytheatre.ie/whatson/overview2008.html. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Neil Bartlett arrived in Ireland for rehearsals on 7th

July, and as part of his very busy schedule, he graciously answered some

questions put by Aoife Leahy on the forthcoming

production for THE OSCHOLARS. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Q. As you begin rehearsals for An Ideal Husband in The Abbey this week, do you have any hints of

what we should expect to see in the new production (14th August – 27th

September with previews 11th–13th August)?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A. Of course, I don’t want to give too much away, but…..

the ‘Society’ plays of Wilde are often thought of as epitomising a certain

kind of well-upholstered, convention-driven late nineteenth century

theatrical heritage product. In fact, the play is subtitled ‘A New and

Original Play of Modern Life’, and it was written in a year when Wilde was

restlessly experimenting with new ways to express both the increasing

turbulence of his private life and his dissatisfaction with conservative

London culture. It was written in the same year as La Sainte Courtisane and

The Florentine Tragedy, two failed experiments in treating An Ideal Husband’s primary themes of

dysfunctional marriage and prostitution, and it comes just before The Importance of Being Earnest –

which is probably the most formally experimental London play of its century.

We’re playing it in period, but trying to keep it as odd, as questioning, as

uncomfortable as Wilde’s letters tell us he found it to write. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Q. Is there a particular resonance to staging a Wilde play

in Dublin? In recent years, Wilde productions have been very popular and well

attended here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A. Of course, as an Englishman, I am slightly apprehensive

about creating the first ever staging of this play at Ireland’s National

Theatre. I just have to remind myself that the play is not only about

outsiders – all the principal characters feel themselves at odds with the

city they live in – but written by a man who revelled in that role. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Q.

Your book Who Was That Man: A Present

for Mr Wilde looks at scandals – including significant gay histories A. Hmmmn, not sure about those ‘good things’- of all

Wilde’s ‘happy endings’, the ending of Act Four of this pay strikes me as

being one of the most queasily double-sided. Of course, in a simple way, the

play is political, even topical – I understand that the notion of a senior

Government figure being caught out over some shady financial transactions is

not entirely unheard of in Dublin. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The entire plot hinges on the

question of whether a corrupt politician should resign or not, so in that

simple sense it is political – thrillingly so…but it is also political in

another and perhaps more interesting sense of the word. It struggles to

connect ideas of personal freedom (and personal guilt and shame) with larger,

social ideas, particularly in the realm of sexual relations and of marriage.

In his own inimitably contradictory and lurid way, Wilde is toying with ideas

that were rising to the surface of his century – in the writings of Symonds,

of Carpenter and of Shaw, for instance, all in the same decade – and giving

them an absolutely personal shape. For obvious reasons, he was obsessed with

the idea of whether personally freedom could ever be found within a

conventional social structure, or whether some more radical shift of values

was the only possible source of salvation…. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Q. You are collaborating with set and costume designer Rae

Smith on the production. Is it important to get the right look and space for

a Wilde play? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A. Absolutely fundamental; this is my eleventh

collaboration with Rae Smith, and artistically the show is as much hers as mine.

The most important thing is to get rid of all notions of decorative décor and

concentrate on telling the story, which is a dramatic and dramatically

unpleasant one. She has taken all of

the conventions – the furniture, the period costumes, even the ideas of

act-drop and scene-change – and made them active ingredients rather than

simply givens. Wilde uses three very different spaces in this story, and Rae

is very good in honing in on what is important about a space from the point

of view of fundamental narrative. For instance, the point about the opening

scene in Grosvenor Square is that the Chiltern’s home is not stable, secure

and luxurious, but built on sand; the point about Lady Chiltern’s morning

room in Act 2 is that it is a feminine and self-consciously conservative

environment, in which the most vicious marital row in Wilde’s entire canon is

spoken (my god, imagine how Constance must have felt watching that scene on

the opening night!!!) whereas Lord Goring’s bachelor pad in Act 3 is

masculine and self-consciously radical….all sounds a bit abstract, but it all

comes down to being bold with colour, light and space. You’ll see! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Q. What do you think of the relatively new Oscar Wilde

statue on Merrion Square (sculpted by Danny Osborne and unveiled in 1997)?

Although Wilde lived in Merrion Square until 1876, Osborne interestingly

portrays him at a later stage in his life. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A. I have tried to love it, I really have, but I’m sorry;

I think the whole idea of a statue to someone as elusive and unstable and

dangerous as Wilde is a bit of a non-starter. He is many things, but

monumental is not one of them. Maggi Hambling’s memorial in London faced the

same problem – and addressed it by making a sort of anti-monument. With some

success; the last time I passed it, it was being sat on by three young and

completely filthy construction workers, using it to have a quick fag in their

tea-break while working on the restoration of St Martin’s church next door,

and the sound of Wilde spinning in his grave (with pleasure, of course) was

actually audible all the way from Paris….. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Q. Any other thoughts or comments? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A. I look forward to seeing you at the show! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Many thanks from The

Oscholars! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aoife Leahy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

X.

BEING TALKED

ABOUT: CONFERENCES & CALLS FOR PAPERS

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here we now only note Calls for Papers or articles

specifically relating to Wilde or his immediate circles. The more

general list has its own page; to reach it, please click |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XI.

OSCAR IN POPULAR CULTURE

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Following in the footsteps of ‘Speranza’, the ‘Wilde Oscars’ and other pop music bands, ‘Dorian Gray’ has a small but Wilde-laden presence on the internet at http://www.doriangrayland.com/. We thank Tiffany Perala for this discovery. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The great progenitors of the incorporation of Oscar Wilde into world of pop music were surely the Rolling Stones, with their song ‘We Love You’. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards wrote this after they were arrested along with Brian Jones on drug charges stemming from a raid on Richards’s house, Redlands, on 12th February 1967. This was a thank you message to the fans who supported Jagger and Richards through their arrest. The Stones made a promotional film for this song that was banned by the BBC but shown elsewhere. It was directed by Peter Whitehead and based on The Trials Of Oscar Wilde with Mick Jagger as Oscar, Keith Richards as the Marquis and Marianne Faithfull as Bosie. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XII.

OSCAR WILDE: THE VIDEO

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Our video this month is The

Canterville Ghost, from a version performed by children. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XIII.

Web Foot Notes

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A look at websites of possible interest.

Contributions welcome here as elsewhere. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All the material that we had thus far published in the

'Web Foot Notes' was brought together in June 2003 in one list called

'Trafficking for Strange Webs'. New websites continue to be reviewed

here, after which they are filed on the Trafficking for Strange Webs page,

which was last updated in May 2008. A

Table of Contents was added for ease of access. ‘Trafficking for Strange Webs’ surveys 48 websites devoted

to Oscar Wilde. The Société

Oscar Wilde is also publishing on its webpages two lists (‘Liens’ and

‘Liaisons’) of recommendations. To see ‘Liens’, click here. To see ‘Liaisons’, click here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We recommend a visit to http://www.dandyism.net/. This represents a serious attempt to get to grips with dandyism, and it is constantly changing. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

http://www.quotationspage.com/quotes/Oscar_Wilde/ is yet another list of phrases taken from Wilde without sourcing them. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

http://www.online-literature.com/wilde/

is a serious attempt to present the works of Oscar Wilde to what we guess

must be American schoolchildren, who use a forum to ask questions about

Wilde. Perhaps rather unfairly, here

are extracts from two of them: ‘Hi!

I'm reading Oscar Wilde's biography in the introduction of the book "The

Importance of Being Earnest." and I came across the history of this

play, Salome. It stated that Salome performed the sensuous "Dance of the

Seven Veils" and I found this quite similar with the dance that Rebecca

Sharp performed with some veiled women in the Vanity Fair movie (starring

Reese Witherspoon) I have yet to read the book by Thackeray so I can't

confirm if The Dance of the Seven Veils was indeed taken from Wilde's Salome.

If anyone could shed light, it would be most welcome.’ ‘Hi, Am thinking about getting into some of

Oscar Wilde's novels, anyone have any recommendations of which i should start

with?’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Daniel Colegate, a third year PhD Student at the

University of Durham has launched a website, www.graduatejunction.com,

designed to help graduate researchers make contact with other researchers

interested in their work. ‘The idea is to connect people who would

otherwise not be aware of each other, perhaps in different groups,

departments, institutions or countries. Increasing communication

can prevent duplication of effort and help the spread of new ideas,

benefiting the entire research community.’

Mr Colegate believes that Graduate Junction could benefit a lot of

graduate researchers, and so do we. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XIV.

OGRAPHIES

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We have recently been expanding our sections of

BIBLIOGRAPHIES, DISCOGRAPHIES and SCENOGRAPHIES and this will be a major

component of our work from now on.

Click the appropriate icons. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XV.

NEVER SPEAKING DISRESPECTFULLY: THE OSCAR

WILDE SOCIETIES & ASSOCIATIONS

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Readers accustomed to checking here for news of the Wilde Societies are advised that these now have their own page. To reach it, please click |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XVI.

OUR FAMILY OF JOURNALS

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All our journals appear on our website www.oscholars.com. Each has a mailing list for alerts to new

issues or special announcements. To be

included on the list for any or all of them, contact oscholars@gmail.com. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Eighth Lamp

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Work goes ahead for the second issue of this journal of

Ruskin studies on our website, under the vigorous editorship of Anuradha Chatterjee (University of South

Australia) and Carmen Casaliggi

(University of Limerick). Dr

Chatterjee has produced a splendid first issue, and issued a Call for Papers

for the second. THE EIGHTH LAMP: Ruskin Studies To-day will shed much light in

new places, and places Ruskin studies firmly in conjugation with Wilde

studies. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rue des Beaux Arts

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The fifteenth issue of our French language journal under the dedicated editorship of Danielle Guérin will be published before the end of July. It continues to reflect and encourage Wilde studies in France and the Francophone countries. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shavings, Moorings and The Sibyl |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

New issues of these journals devoted to George Bernard Shaw (co-edited by Barbara Pfeifer), George Moore (edited by Mark Llewellyn) and Vernon Lee (edited by Sophie Geoffroy) are planned for this autumn. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Visions and Nocturne |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the spring of 2008 we gathered together all the visual arts information that was scattered through different section of THE OSCHOLARS into a section called VISIONS. This was consolidated in the summer, and a new edition is planned for the autumn. Subsequently we will be calling for papers. VISIONS is co-edited by Isa Bickman, Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch, Nicola Gauld and Sarah Turner. NOCTURNE, our journal devoted to Whistler and his circle, remains in abeyance for the time being. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Latchkey |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In September /October we will launch THE LATCHKEY, a journal devoted to reporting and creating scholarship on The New Woman. The co-editors are Jessica Cox, Petra Dierkes-Thrun, Sophie Geoffroy, Lisa Hager, Christine Huguet, and Alison Laurie. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XVII. Acknowledgements |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE OSCHOLARS website continues to be provided and constructed by Steven Halliwell of The Rivendale Press, a publishing house with a special interest in the fin-de-siècle. Mr Halliwell joins Dr John Phelps of Goldsmiths College, University of London, and Mr Patrick O’Sullivan of the Irish Diaspora Net as one of the godfathers without whom THE OSCHOLARS could not have appeared on the web in any useful form. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Digest of the Victorian

Gothic and Decadent Literature, edited for THE OSCHOLARS by Sondeep Kandola (University of

Leeds). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[We

incorporate this first digest into our Editorial page, in the expectation

that for the second issue it will move to its own page within www.oscholars.com, to be linked from here

or reached from the drop-down menu – Ed. THE OSCHOLARS] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Glennis Byron on Bram

Stoker, a Literary Life by Lisa Hopkins |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

John Plunkett on Jack

the Ripper: Media, Culture, History

(eds.) Alexandra Warwick and Martin Willis |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ruth

Robbins on The Routledge Companion to the Gothic (eds.) Catherine Spooner and Emma McEvoy and Gothic Literature by Andrew Smith |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Andrew Tate on Catholicism,

Sexual Deviance and Victorian Gothic Culture by Patrick R. O’Malley |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Calls for Papers: Decadence at the

Transatlantic Fin de Siècle |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gothic Excess |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Transatlantic Decadence |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Realism and the Supernatural in the Nineteenth

Century |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Phobia: Constructing the Phenomenology of Chronic

Fear, 1789 to the Present |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstracts |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nick Freeman on Arthur Machen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Minna Vuohelainen on Richard Marsh |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Emily

Alder on Algernon Blackwood and

William Hope Hodgson |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

REVIEWS: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Review by

Glennis Byron

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lisa

Hopkins, Bram Stoker: A Literary Life .Palgrave, 2007. ISBN 13:

978-1-4039-4647 (Hb). 173pp. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

While Stoker is remembered for one

book when he wrote seventeen others, Lisa Hopkins argues in her introduction

to Bram Stoker: A Literary Life,

‘there is a sense in which he wrote Dracula many times over and called it a

variety of things’ (1). The rest of the introduction may have the unfortunate

effect of alienating many readers, as the numerous lists and descriptions of

various connections between Stoker’s works are rather overdone, and one waits

in some frustration for the arguments and analysis to begin. However, for

those who persist, this book has much to offer. Hopkins has certainly found

an impressive number of similarities between Stoker’s fictional works, and,

focusing on a number of key issues, ultimately provides a far more detailed

and convincing exploration of the relationship of the author’s work to his

life than many conventional biographies of Stoker have offered. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following four chapters focus

on the impact on Stoker’s work of, respectively, his early life in Dublin;