|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

An Electronic Journal for the Exchange of Information |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

on Current Research, Publications and Productions |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Concerning |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oscar Wilde and His Worlds |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Issue no 47 : November / December 2008 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

EDITORIAL PAGE |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Navigating THE OSCHOLARS |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Since November 2007 split this page has been split into two sections. SECTION I now contains our Editorial, short pieces that we hope will interest readers, and innovations. SECTION II is a Guide or site-map to what will be found on other pages of THE OSCHOLARS with explanatory notes and links to those pages (formerly to be found on the Editorial page). Each section is prefaced by a Table of Contents with hyper links to the Contents themselves. For Section I, please read on. |

Clicking clicking clicking

The sunflower |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE OSCHOLARS is composed in Bookman Old Style, chiefly 10 point. You can adjust the size by using the text size command in the View menu of your browser, Internet Explorer being recommended. We do not usually publish e-mail addresses in full but the sign @ will bring up an e-mail form. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nothing in THE OSCHOLARS © is copyright to the Journal save its name (although it may be to individual contributors) unless indicated by ©, and the usual etiquette of attribution will doubtless be observed. Please feel free to download it, re-format it, print it, store it electronically whole or in part, copy and paste parts of it, and (of course) forward it to colleagues. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As usual, names emboldened in the text are those of subscribers to THE OSCHOLARS, who may be contacted through oscholars@gmail.com. Text in blue can be clicked for navigation. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

I. NEWS FROM THE EDITOR |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Innovations |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Since our last issue we have again strengthened our

Editorial team, reflecting and contributing to our ever-increasing coverage

of period and topics. More information

about them can be found by clicking |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

·

Gwen

Orel, a New York theatre critic, has taken over from Patricia Flanagan Behrendt as American Theatre Editor. Patricia

will continue to contribute other material from the United States for

us. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A major innovation is the introduction of a new section: our Colour Supplement. Some will remember a strip cartoon by Dan Pearce called ‘The Millennium Man’ that appeared on the Internet some years ago and subsequently disappeared again. Click the illustration to take up the tale: |

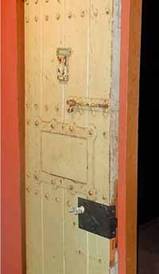

Pictured: The original door of cell C.3.3, Reading Gaol, now part of the HM Prison Service Collection housed at the Galleries of Justice, Nottingham. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This issue contains the second supplement dealing with late Victorian Gothic as a trope of decadence – MELMOTH, edited by Sondeep Kandola. This comes at the end of this page. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Our special supplement on Teleny, was published in

October 2008. This was guest edited by Professor John McRae of

the University of Nottingham, whose edition of Teleny was the first

scholarly unexpurgated one to be published. Teleny Revisited now

becomes a major on-line resource and further articles will be considered for

publication. Contact Professor

McRae @; see Teleny Revisited |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

So many chances and changes have necessitated constant revisions in our publishing schedules, with only RUE DES BEAUX ARTS under Danielle Guérin’s editorship maintaining its intended two-monthly appearance on time, although THE OSCHOLARS seems back on track with an intended appearance in two-monthly instalments (the last was September/October). This has been balanced by our publishing new content on our website nearly every day, and announcing this in weekly reports on our ‘yahoo’ subsidiary. The number of our readers who have joined this has been growing, and it is increasingly our medium for making announcements in the place of mass mailings, which more and more fall foul of anti-spam traps either at the sending or receiving end. We do urge readers to sign up to this group. Our NOTICEBOARD also serves all our journals. Here we publish short term announcements of lectures, publications, papers and other items of interest submitted by readers. This does not replace notice in any of the journals, but is intended to be of value between issues. The ‘yahoo’ forum and NOTICEBOARD can be reached via their icons: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

II. THE OSCHOLARS LIBRARY |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

III.

FREQUENTING THE SOCIETY OF THE AGED AND

WELL-INFORMED: NEWS, NOTES, QUERIES.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

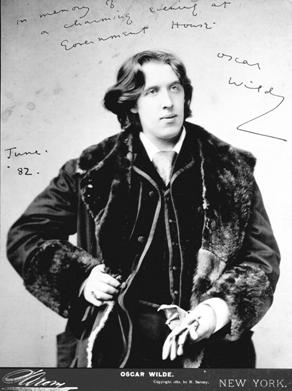

Notes Towards an Iconography of Oscar

Wilde.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One of the least known portraits of Wilde, we think, is the drawing by Boldini, shown at the exhibition ‘Marcel Proust and His Time’, at the Wildenstein Gallery, 147 New Bond Street, London, in 1955. This was reproduced the Exhibition Catalogue, where it is plate XIII. The catalogue number, 176, is reticent, revealing only that it was lent by a Dr Robert Le Masle. More information on this is eagerly sought. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lady Wilde |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I’m looking for any critical studies done on Meinhold’s

work - The Amber Witch and Sidonia the Sorceress. I’m aware only

of the Diana Basham book The Trial of

Woman – which briefly covers Amber Witch - and a few mentions in more

recent articles. Is there anything written on these works at all? I’m also

very interested to find any comments - correspondence etc – from the two

translators of the novels – Duff-Gordon for the Amber Witch, and Lady Wilde

on Sidonia. Any |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

n Jodi Gallagher @ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oscar Wilde and the Oxford Companions (2) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Concise Oxford

Dictionary of French Literature, edited by Joyce M.H. Reid (Oxford:

Oxford University Press 1976) has a brief article of five lines on Wilde: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wilde, Oscar (1854-1900), the Anglo-Irish poet and

dramatist, had many association with French literary circles and latterly

lived, and died, in Paris. He wrote his Salomé

in French in the first instance. [p.665]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There is also

an eight-line entry for Salomé, p.571. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French, edited by Peter France (Oxford: The Clarendon Press 1995) has no article on Wilde or Salomé. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Broadcasts |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Salomé of

Florent Schmitt was broadcast on France Musique and other European wireless

channels on 4th December; The

Nightingale and the Rose was broadcast

on the wireless station BBC 7, on 7th December. We announced these at the

time on our forum, and hope that we can extend these notifications about

broadcasts with the help of readers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Work in Progress |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In December 2006 we published a list of fin-de-siècle doctoral theses being undertaken at Birkbeck College, University of London, and a similar list in December 2007. Naturally we hoped to bring this up to date for the current academic year, but a fairly prolonged examination of the Birkbeck site was unable to locate the list. We will inquire. We should very much like to hear from readers at other universities with news of similar theses they are supervising or undertaking. We welcome all news of research being undertaken on any aspect of the fin de siècle. There is a list of dissertations on Irish literature held on the Princess Grace Irish Library website (http://www.pgil-eirdata.org/html/pgil_gazette/disserts/a/) but it seems to be impossible to gain access. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Wilde Collection |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There is no universal handbook or vade mecum to the various Wilde Collections, and we have made a start here with an occasional article. Sometimes where a collection’s contents are published in detail on-line we will simply give an URL; or we may be able to give more details ourselves. We will then to be able to bring these together as a new Appendix. We would be very interested in publishing account of privately held collections, suppressing the owner’s name if that is preferred. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 1891, an Oxford

undergraduate named Bernulf Clegg, having read The Picture of Dorian Gray, wrote to Wilde asking him where in

his other work he ‘may find developed that idea of the total uselessness of

all art.’ Wilde, not directly

answering Clegg’s question, responded: ‘Art is useless because its aim is

simply to create a mood. It is not meant to instruct or influence action in

any way. It is superbly sterile, and the note of its pleasure is sterility.’ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As has been widely reported in

the international press, the letters of Wilde and Clegg, along with some 50

handwritten pages, including nine manuscripts of Wilde’s poems and the

earliest surviving letter from Wilde to Lord Alfred Douglas, are contained in

a red leatherbound volume that was recently given to the Morgan Library &

Museum by Lucia Moreira Salles, a Brazilian philanthropist who had owned it

for more than two decades. Its whereabouts were unknown to scholars for half

a century. Mrs Moreira Salles owned the volume with her husband, Walter Moreira

Salles, a Brazilian banker and diplomat who died in 2001. The book also

includes a manuscript of Wilde’s short story for children ‘The Selfish Giant,’

handwritten by Wilde’s wife, Constance.

Two letters to Douglas are given in the Nouvel Observateur. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘The contents are remarkable,’

William M. Griswold, the director of the Morgan, is quoted as saying. He

added that the gift was particularly significant because, in addition to its

collection of letters by Wilde, the Morgan also owns the earliest manuscript

of The Picture of Dorian Gray. Mr Griswold said he learned of the volume’s

existence shortly after Christine Nelson, a curator of manuscripts at the

Morgan, was contacted by Merlin Holland at the Morgan, which in 2001

organized the exhibition ‘Oscar Wilde: A Life in Six Acts,’ in collaboration

with the British Library. About two

years ago Mrs Moreira Salles contacted Mr Holland to see if he would be

interested in editing a facsimile of the book. He in turn told her about the

Morgan’s extensive holdings of Wilde’s letters and manuscripts. This summer,

Mrs Moreira Salles decided to donate the book to the Morgan. ‘It was one of those happy surprises,’ Ms

Nelson said. ‘It was last seen in a 1953 London sale catalogue.’ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Morgan plans to show the

volume in an exhibition of acquisitions from 17th April to 9th August 2009. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

News from the Royal Historical Society Bibliography, Irish History Online

AND London’s Past Online

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We have introduced new links to the detailed display of records for books and for recent articles in books. These links search Google Books for the work that you are viewing. If you follow the link you will be presented with a Google results page which tells you if there are any results and also indicates whether you can see online text, and, if so, whether full or limited view is available. See our help pages. We would welcome your feedback on the effectiveness and usefulness of these links – you can use the feedback form, or send an e-mail to @. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tutorials: To help you to get the most out of the

Bibliography, the RHS Bibliography has introduced new tutorials, that you can

either view online or download to your own computer as Word documents or in

pdf format. Please go to our Tutorials page for

more information. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IV. OSCAR WILDE : THE POETIC LEGACY |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Irish poet Paul Muldoon has been described by Stephen

Knight in the TLS as ‘the most

significant English language poet born since the Second World War’ and by

Ruth Padel in The Guardian as ‘possibly

the biggest influence on all original British poets who began writing after

the mid-seventies’. His poem Two Stabs at Oscar appeared in his

collection Moy Sand and Gravel

(London: Faber & Faber 2002 p.65), and is here reproduced by kind

permission of the author. |

Two STABS

AT OSCAR i As I roved out between a gaol and a river in spate in June as like as January I happened on a gate which, though it lay wide open, would make me hesitate. I was so long a prisoner That, though I am now free, the thought that I serve some

sentence is so ingrained in me that I still wait for a warder to come and turn the key. II A stone breaker on his stone bed lay no less tightly curled than opposite–leaved saxifrage that even now, unfurled, has broken through its wall of

walls into this other world. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

V. on the Curriculum : Teaching Wilde, Æstheticism and Decadence. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We are always anxious to publicise the teaching of Wilde

at both second and third level, and welcome news of Wilde on curricula.

Similarly, news of the other subjects on whom we are publishing (Whistler,

Shaw, Ruskin, George Moore and Vernon Lee) is also welcome. Andrew

Eastham is developing a study of the teaching of Wilde, which we hope

will be helpful to others who have Wilde on their courses; in tandem Tiffany Thomas is looking at

undergraduate response. Andrew Eastham

presented his introductory declaration in our July/August issue |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Programs & Initiatives – Moments of Change – 2008-09: The Turn of the 20th Century (1889-1914). This is a course at Penn State University. Consult http://iah.psu.edu/programs/early20thCentury.shtml. The course co-ordinator is Martina Kolb, Assistant Professor of German and Comparative Literature. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A list of website |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

VI. THE

CRITIC AS CRITIC

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This issue’s review section contains reviews by Gert Buelens on Michèle Mendelssohn on Henry James and Oscar Wilde; Gwen Orel on The Selfish Giant and An Ideal Husband in New York; Leonée Ormond on Molly-Whittington-Egan on Frank Miles and Oscar Wilde; Linda Dryden on W.E. Henley and Robert Louis Stevenson; John McRae on Hirschfeld and Roellig on Homosexuals in Berlin; Laurence Talairach-Vielmas on John Glendening on The Evolutionary Imagination; Richard Toye on John Partington on H.G. Wells. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Last issue’s review section contained reviews by Aoife Leahy on An Ideal Husband in Dublin; Mathilde Mazau on Dorian Gray in Edinburgh; Gwen Orel on The Selfish Giant in New York; Ruth Kinna on David Goodway on Anarchism; Lucia Krämer on Angela Kingston on Oscar Wilde; John S. Partington on Ruth Livesey on Socialism and Æstheticism; Kathleen Riley on Christopher Stray on Gilbert Murray; Annabel Rutherford on Mary Fleischer on Symbolist Dance; Eva Thienpont on André Capiteyn on Maeterlinck; Jessica Wardhaugh on Sébastien Rutés on Oscar Wilde and French Anarchism. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Clicking |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

VII. DANDIES,

DRESS AND FASHION

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Editor for this section: Elizabeth McCollum |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

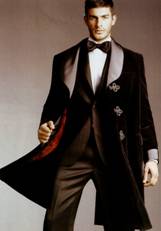

We recommend a visit to http://www.dandyism.net/. This represents a serious attempt to get to grips with dandyism, and blends the disciplines of a magazine and a website. We cull this snippet, only commenting that it is a pity that the young man forfeits any dandiacal status by apparently wearing a made-up bow tie and having forgotten to shave: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Brioni has apparently raided the 1880s wardrobe of Oscar Wilde for inspiration. Its latest advertisement in Men’s Vogue features this Bunthornian velvet topcoat with shawl collar and embroidered button fastenings.’ |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘Swann & Oscar’ pairs

Proust’s Charles Swann with Oscar Wilde as the name of a gentleman’s

outfitter at 19 rue d’Anjou in the fashionable eighth arrondissement

of Paris, adding an echo of London’s Swan & Edgar. Click their banner. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

VIII. OSCAR WILDE AND THE KINEMATOGRAPH

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the Rome Film Festival which ended on 31st October

2008, Al Pacino showed a pre-première few minutes

montage of his long-awaited Salomaybe.

Release is planned for 2009 with the following cast: Al Pacino, Serdar Kalsin

(himself / Herod), Kevin Anderson (himself / Jokanaan), Jessica Chastain,

Estelle Parson (Salomé), Roxanne Hart (Herodias), Philipp Rhys (the young

Syrian), Jack Huston (Lord Alfred), Richard Cox (Robert Ross)… |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

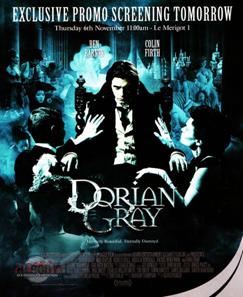

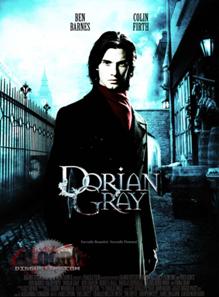

The English actress Rebecca Hall has joined the cast of Oliver Parker’s Dorian Gray in the rôle of Sibyl Vane. She shares th cast with Ben Barnes (Dorian), Colin

Firth (Lord Harry), Ben Chaplin and Rachel Hurd. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Posters |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IX. LETTERS FROM OUR EDITORS

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Koenraad Claes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dear Oscholars |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Although it has

taken me a while to gather a few interesting titbits on fin-de-siècle events

in Belgium, I have still found hardly anything relating to specifically ‘Belgian’ topics. It is surprising to see that my humble country, usually quite

hung up on its late-nineteenth-century fame, this past Autumn seems to have

directed its attention to other periods and schools. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Not as

surprising, however, as the news that reached me this week about a Walloon

theatre troupe tackling one of the most eccentric French plays in a rather

provincial venue. The collective Rives d’Art will perform my beloved Ubu Roi this weekend (13th-14th

December), at the Auvelais cultural centre in the charming town of

Sambreville. Their aim is to show that the bleak world of Alfred Jarry is

still very much our own. The naughty disclaimer ‘que toute ressemblance avec des situations

ou des personnages existants serait tout à fait volontaire’ probably indicates that some inspiration

has been found in the notorious surrealism of contemporary (Belgian)

politics. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In October, a

brighter view of the end of the French nineteenth century was presented at

two lunchtime concerts, entitled ‘Belle Époque’. On

Wednesday the 22nd at the Opera of Antwerp, and on Friday the 24th in Ghent,

rising Portuguese soprano Ana Quintans and mezzo-soprano Inez Carsauw brought

art songs by Fauré, Debussy, Satie and Reynaldo Hahn. They were skilfully

supported by pianist Jef Smits, a staple of classical music in Flanders. The

unique repertoire, and its elegant delivery, made all who attended hope that

more of such initiatives would follow in the near future. These particular

concerts were part of the ‘Quinzaine

Française - Antwerpen 2008’,

the second edition of an annual multidisciplinary cultural festival organized

by the French consulate to Belgium and the city of Antwerp. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another event

that was given some press attention, was the temporary relocation of the

well-known sculpture of Balzac by Rodin, which for two months found a home in

the Middelheim gardens of Antwerp. This open-air museum has a permanent

exhibition of some 200 sculptures, among which another Rodin and several more

artistic highlights. During the stay of this eminent visitor, an accompanying exposition was held on the

genesis and history of the sculpture, with background information on both

sculptor and sculpted. By 15th December it will return to its regular spot in

the Royal Art Museum of Antwerp (KMSKA). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism, an international cooperation with strong Belgian connections, was officially launched in the British Library on Monday 8th December. Editors Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor chose the Ghent-based Academia Press to publish this reference work in joint venture with the British Library, and it has been partly funded by Flemish grants. Even if Professor Demoor were not my supervisor at Ghent University, I would have been very excited about this book. Its ODNB-style presentation makes it highly practical in use, and it contains an abundance of information on people, periodicals and topics of the nineteenth-century press. The Nineties have not at all been neglected, as besides on Oscar Wilde (naturally), we find – among many others - individual entries on Woman’s World, Ella Hepworth Dixon, John Lane, Charles Ricketts, Charles Shannon, Ella D’Arcy, Richard Le Gallienne, Leonard Smithers, William Sharp, Alice Meynell, Rosamund Marriott Watson, G.B. Shaw, Gleeson White, Arthur Symons, Vernon Lee, Frank Vizetelly, Aubrey Beardsley, and the Yellow Book, Savoy, Pageant, Dial, Hobby-Horse and Dome. It will no doubt be seen as an additional asset that several Oscholars have contributed to this volume. A web-based version of the book will shortly be added to the C19: The Nineteenth Century module of ProQuest, which already hosts the invaluable Wellesley Index and the British Periodicals database. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aoife Leahy |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Christmas greetings from Ireland to all of the Oscholars. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On the subject, of Christmas, there will be a ‘Warming Words at Christmas Time’ story reading at The New Theatre inside Connolly Books, Temple Bar, Dublin as part of a programme of seasonal Temple Bar events. Children’s author Catherine Ann Cullen will read a variety of stories including Wilde’s ‘The Selfish Giant’ on 13th December at 1.15pm. See http://www.templebar.ie/home and click on Christmas Programme. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cork born actress Fiona Shaw, who was recently seen in Beckett’s Happy Days in The Abbey Theatre, has joined the cast of Oliver Parker’s new film adaptation of The Picture of Dorian Gray. Various sources report that Shaw will play ‘Agatha’, presumably meaning that we will see her as Lord Henry’s Aunt Agatha. Although Aunt Agatha is a relatively minor character in the novella, she brings various elements of the plot together. Lord Henry’s first gossip about Dorian comes from his aunt, who hopes that the young man with the beautiful nature will assist with her charitable projects in London’s East End. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I contributed a paper entitled ‘Wilde Over There’ at The Irish Diaspora Conference in the University of Limerick on the 1st of November 2008. The paper focused on Wilde’s 1882 tour of America and Canada and his subsequent comments on the better quality of life in America for the working man and the poor. The Irish Diaspora Conference was organised by Dr Tina O’Toole, Dr Kathryn Laing, Dr Caoilfhinn Ní Bheachtáin, Ms Yvonne O’Keeffe and Ms Heather Goggans. Many international scholars attended and gave papers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Department of English in NUI Maynooth has announced that Dr Deaglán Ó Donghaile has been awarded a Clark Library Short Term Fellowship to carry out research on Wilde in the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California in April 2009. The Clark Library holds the collection ‘Oscar Wilde and the 1890s.’ See http://english.nuim.ie/news.shtml |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The entertainment production company Arcana has made a ‘Massive Head’ of Oscar Wilde that can be worn by brave tour guides on scheduled Walkabouts of Dublin Streets and Cultural Organisations. In Hiberno-English slang, massive means both ‘enormous’ and ‘marvellous’! A photograph of the Massive Head Wilde with a Massive Head Brendan Behan and a Massive Head James Joyce can be found on http://culturenight.ie/detail.asp?ID=165. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Irish Ferries website describes the company’s newest ship The Oscar Wilde as ‘the most luxurious ship to sail between Rosslare and France.’ The car ferry Wilde ship has 11 decks and can accommodate 1458 passengers and 580 cars. Oscholars who would like to sail in The Oscar Wilde can look at http://www.irishferries.com/ships-oscarwilde.asp for more information. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Atsuko Ogane |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(translated

and summarised from the French by D.C. Rose) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For this my first Letter, I attended the 33rd Annual Congress of the Japanese Oscar Wilde Association, held on the 6th December at Komazaswa University in central Tokyo. I was able to address the Association on behalf of THE OSCHOLARS and the Société Oscar Wilde en France, and this rapport was welcomed. My report on the proceedings of the Congress is given on the page of THE OSCHOLARS devoted to Wilde Societies; in subsequent letters I will report on the state of Wilde studies in Japan. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tijana Stajic |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greetings from Sweden to all of the Oscholars! I am delighted to have a chance to communicate news on our common enthusiasm for Oscar Wilde and related matters. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wilde and fin de siècle continue to attract scholarly attention as well as popular interest in Sweden. The biggest event recently was a plenary lecture at the conference ‘Urban and Rural Landscapes: Language, Literature, and Culture in Modern Ireland’ at DUCIS, Dalarna University, November 6-7 2008, given by professor Jarlath Killeen of Trinity College, Dublin. Entitled ‘Oscar Wilde, the Irish Land Struggle, and Fairy-Tale Solutions: The Case of ‘The Selfish Giant,’’ the lecture offered Wilde’s fairy tale as a metaphor for ownership and potentially a paradigm of solutions to land conflicts in Ireland. For more information on the conference, please see http://www.du.se/templates/Page____7524.aspx?epslanguage=SV. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Professor Killeen also chaired the panel entitled ‘Visible Mysteries: Irish Literature and Photography from the Fin de Siècle to the Early Twentieth Century’ that offered two papers: ‘Picturing Darkest Dublin: Photography and the Geography of Poverty, 1980-1913’ by Justin Carville from the institute of Art, Design and technology, Dun Laoghaire, Dublin, and ‘Fatal Misreading of the Work of Art in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray’ by Tijana Stajic from the University of Gothenburg. The entire conference has been streamed and the contributions above can be specifically seen at mms://media.du.se/2008ht/Konferens/081107_ducis_4_fo5.wmv. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another piece of research inspired by fin de siècle is Sofia Wijkmark’s thesis presented at a final

seminar at th University of Gothenburg, 28th November. Originally from

Karlstad University, Wijkmark has written a thesis on gothic elements in the

shorter fiction by a Swedish female author Selma Lagerlöf (1858-1949) who was

awarded a Nobel Prize in 1909. Wijkmark’s thesis deals with, among other

texts, Osynliga länkar (The Outlaws) (1894), En herrgårdssägen (A Legend of the Country Manor) (1899),

Mårbacka (1922) and Löwensköldska ringen (The Ring of the Löwenskölds) (1925). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wilde continues to attract the attention of undergraduate students, and so another paper, originally written in 2004, and addressing the decadent theme, is recently made available at the Swedish website for undergraduate research work www.uppsatser.se. The author is Jenny Siméus of Växjö University and the title of the paper is ‘A Study of Art and Aestheticism in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray’. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The daily newspaper ‘Trelleborgs Allehanda’ from southern

Sweden published 29th October an article entitled ‘Wilde ska locka forskare

till Ystad’ (‘Wilde is Supposed to Attract Researchers to Ystad’) about the

City library, which possesses about 1,900 books primarily by or about Wilde,

as well as some other contemporaneous figures such as Aubrey Beardsley.

Originally donated by the librarian John Andrén (1897-1965), the books are a

part of the so-called Andrén collection and may present an important source

for international researchers. In order to attract scholars, the foundation

has employed the researcher Lena Olsson who works at cataloguing the titles

and suggestions for the acquisition of new books. For the original article,

please see www.trelleborgsallehanda.se. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Besides scholarly work, Oscar Wilde still inspires popular

culture and frames important gender issues in Sweden. In August 2008 appeared

the first issue of ‘Dorian’, the first gay magazine in the country. The sub-title

‘Gay Life in Style’ best defines the main preoccupations of the journal:

travels, beauty products, fashion, celebrity interviews, and sex, all appear

in a sophisticated frame, and with illustrations à la Aubrey Beardsley. For

more information, please check www.dorianmagazine.com. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

X. BEING

TALKED ABOUT: CONFERENCES & CALLS FOR PAPERS

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here we now only note Calls for Papers or articles

specifically relating to Wilde or his immediate circles. The more

general list has its own page, updated every month; to reach it, please click

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oscar Wilde has become a legend: an outstanding and witty dandy who was a real success in society dinners, but also a man whose image is tainted by scandal and provocation. The recent publication of several biographies, among which Richard Ellmann’s is seen as a reference, as well as letters and the detailed account of his trial by his grandson Merlin Holland (A Life in Letters, 2003 and The Real Trial of Oscar Wilde, 2003), all seem to indicate a desire for historical truth to be eventually revealed in a world now freed from homophobia. But once more, the analyses shed light on a character, a man and the role he created for himself. They do not offer a thorough analysis of his work. Actually one of the numerous aphorisms which Oscar Wilde is famous for, according to which life imitates art, and which he developed in his dramatic monologue De Profundis must not overshadow the primary importance of his literary and artistic creation. This issue of the Cahiers Victoriens et Edouardiens devoted to Oscar Wilde’s theatre aims at a return to the stylistic analysis of his plays, which were too often dismissed as trivial and considered as light entertainment for the higher classes of Victorian society. We will try to show how rich and creative his writing is, combining light comedy and poetic drama. Moreover, as a milestone and authoritative work of lasting significance, Wilde’s theatre is very often performed today: how can one explain that plays so deeply- rooted in the Victorian era, representing outdated social and moral values, are still arousing the interest of stage directors and gathering a faithful audience? We will thus study how stage directors adapt his plays to find a new public. As a playwright, but also as a stage director of his own public and private life and as a performer of a variety of roles, Oscar Wilde is above all a man of the theatre. This issue of the Cahiers Victoriens et Edouardiens will thus try to avoid a mere biographical point of view to put his theatrical creation itself on the front stage. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A CV and an abstract in English (no more than 300 words) should be sent by 30th March 2009 to Marianne Drugeon, special editor of this issue. Marianne.drugeon@univ-montp3.fr The article should follow the presentation of the M.L.A.Handbook. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Notes for contributors: Articles submitted for consideration. Length: 30 to 40,000 characters (6000 to 7000 words). Two hard-copies of the article should be sent along with the e-mail copy to Marianne Drugeon. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

M.L.A. Style Sheet Specifications; Rich Text Format (RTF). Use footnotes, not endnotes. Illustrations are welcome but the author is responsible for obtaining all necessary copyright permissions before publication. The bibliography should come at the end of the article. For more details and to send your submission, please contact: Marianne.drugeon@univ-montp3.fr |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Marianne Drugeon, MCF, Special Editor of the CVE, Université Montpellier 3, Route de Mende, 34199 Montpellier Cedex 5 FRANCE. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XI. OSCAR

IN POPULAR CULTURE / WILDE AS UNPOPULAR CULTURE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alcohol

taken in sufficient quantities (1): |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following letter has been received from one of our readers: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘…I wanted to alert you to something, if you are not already aware of it. I attempted to go to the OScholars’ website from my public library in Tacoma, Washington, USA, and it was blocked because, the warning message said, the site is “pornographic”!!! I guess I will have to wait until I am home in North Carolina to view the site, but how distressing!’ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XII.

OSCAR WILDE: THE VIDEO

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Our video this month is ‘The Ghost of Canterville Hall…Oscar Wilde’s play put on by the Rocky Mountain Theater for Kids’, Boulder, Colorado, 27th & 28th October 2007. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We also draw readers’ attention to the

videos in the Theatre Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. These can only be viewed in the Museum’s

Reading Room, a restriction imposed as part of the recording conditions. To date the videos are The Importance Of

Being Earnest, Old Vic Theatre, August 1995 directed by Terry Hands; The

Importance Of Being Oscar by

Michéal Mac Liammoir, Savoy

Theatre, May 1997, directed by Patrick Garland with Simon Callow as Mac

Liammoir as Wilde; and Lady Windermere’s Fan, Theatre Royal Haymarket, May 2002,

directed by Peter Hall. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XIII. Web

Foot Notes

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A look at websites of possible interest.

Contributions welcome here as elsewhere. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All the material that we had thus far published in the

‘Web Foot Notes’ was brought together in June 2003 in one list called

‘Trafficking for Strange Webs’. New websites continue to be reviewed

here, after which they are filed on the Trafficking for Strange Webs page,

which was last updated in May 2008: a new update is in the course of

preparation. A Table of Contents has

been added for ease of access. ‘Trafficking for Strange

Webs’ surveys 48 websites devoted to Oscar Wilde. The Société Oscar Wilde is also

publishing on its webpages two lists (‘Liens’ and ‘Liaisons’) of recommendations.

To see ‘Liens’,

click here. To see ‘Liaisons’, click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We recommend two websites of fin-de-siècle theatre

interest. The first is devoted to

Lillie Langtry: www.hurstmereclose.freeserve.co.uk/html/lillie_langtry.html. The second is a good bibliography about

Sarah Bernhardt: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Andrew Martin of the Irish Newspaper Archive has announced the opening of the ‘largest online database of Irish Newspapers ever published on the Internet, 1763 to the present. Institutions can search, retrieve and view Ireland's past in the exact format as it was published ... the most comprehensive and complete Irish Newspaper archive in the world. Each word is retrievable and every paper is date ranged indexed by title, date month and year. The resource now covers the majority of Ireland's counties and continues to grow on a monthly basis.’ www.IrishNewspaperArchives.com. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Irish History Online is an authoritative guide (in progress) to what has been written about Irish history from earliest times to the present. It has been established in association with the Royal Historical Society Bibliography of British and Irish History (of which it is now the Irish component) and London's Past Online. Since the most recent update (February 2008) IHO contains over 63,000 items, drawn mostly from Writings on Irish History, and covering publications from 1936 to 2004 (in progress). In addition, it contains all the Irish material currently held on the online Royal Historical Society Bibliography. (The latter is less comprehensive but covers a longer period of publications, up to the most recent). In summer 2008, publications for 2005 will be made available for online searching. During the current phase of funding from the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences (2006-9), particular attention is being paid to enhancing coverage of the Irish abroad: at the most recent update almost 500 new records on the Irish abroad were added, including many references collected in libraries in the U.S.A. and Canada. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XIV. OGRAPHIES

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We continue to expand our sections of BIBLIOGRAPHIES, DISCOGRAPHIES and SCENOGRAPHIES and this is now a major component of our work. Click the appropriate icons. Updates are announced regularly on our forum. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XV. NEVER

SPEAKING DISRESPECTFULLY: THE OSCAR WILDE SOCIETIES & ASSOCIATIONS

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

News of the Wilde Societies is published on their own page. We are very pleased that we now (December 2008) carry news of the Oscar Wilde Society of Japan. To reach the page, please click |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XVI. THE

OSCHOLARS COLOUR SUPPLEMENT

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Readers of our sister journal RUE DES BEAUX ARTS will be

familiar with its long running strip cartoon on Oscar Wilde by Patrick

Chambon. In the issue of November 2008

this was joined by a new strip by Dan

Pearce, translated into French (as

Oscar Wilde: La Resurrection) by Danielle

Guérin. With this issue of THE OSCHOLARS we begin its

serialisation in English (as Oscar Wilde: The Second Coming).

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Our hope is eventually to bring all three strips into one folder, where they can be read straight through as graphic novels. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

· For a Bibliography of Wilde in graphic novel form compiled by Danielle Guérin, click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XVII. OUR FAMILY OF JOURNALS

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All our journals appear on our website www.oscholars.com. Each has a mailing list for alerts to new issues or special announcements. To be included on the list for any or all of them, contact oscholars@gmail.com. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Eighth Lamp

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The second issue of this journal of Ruskin studies has

been published on our website, under the vigorous editorship of Anuradha Chatterjee (University of

South Australia) and Carmen Casaliggi

(University of Limerick). Dr

Chatterjee has produced a splendid new issue, and issued a Call for Papers

for the third. THE EIGHTH LAMP: Ruskin Studies To-day will shed much light in

new places, and places Ruskin studies firmly in conjugation with Wilde

studies. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rue des Beaux Arts

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The seventeenth issue of our French language journal under the dedicated editorship of Danielle Guérin was published before the end of November. It continues to reflect and encourage Wilde studies in France and the Francophone countries. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shavings, Moorings and The Sibyl

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

New issues of these journals devoted to George Bernard Shaw (co-edited by Barbara Pfeifer), George Moore (edited by Mark Llewellyn) and Vernon Lee (edited by Sophie Geoffroy) are published as material is accumulated. We recommend joining their mailing list for alerts. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Visions and Nocturne

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the spring of 2008 we gathered together all the visual arts information that was scattered through different section of THE OSCHOLARS into a section called VISIONS. The third edition was published this autumn and a new one is planned for the spring. Subsequently we will be calling for papers. VISIONS is co-edited by Anne Anderson, Isa Bickman, Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch, Nicola Gauld and Sarah Turner. NOCTURNE, our journal devoted to Whistler and his circle, is now being incorporated into VISIONS. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Latchkey

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

After various teething problems, the first issue of THE LATCHKEY, a journal devoted to reporting and creating scholarship on The New Woman, is now ready for publication. The co-editors are Jessica Cox, Petra Dierkes-Thrun, Sophie Geoffroy, Lisa Hager, Christine Huguet, Kathleen Gledhill and Alison Laurie. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XVIII. Acknowledgments

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE OSCHOLARS website continues to be provided and

constructed by Steven Halliwell of The Rivendale Press, a

publishing house with a special interest in the fin-de-siècle. Mr

Halliwell joins Dr John Phelps of Goldsmiths College, University of

London, and Mr Patrick O’Sullivan of the Irish Diaspora Net as one of

the godfathers without whom THE OSCHOLARS could not have appeared on

the web in any useful form. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Return to Table of Contents |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Melmoth |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Digest of the

Victorian Gothic and Decadent Literature |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Edited by Sondeep Kandola, University of Leeds |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

No. 2: November 2008 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For Melmoth

no.1, please click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews: |

Andrew Eastham on Decadence in the Late Novels of Henry James by Anna Kventsel |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Stefano Evangelista

on Art and the Transitional Object in

Vernon Lee’s Supernatural Tales by Patricia

Pulham |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstracts: |

Fiona Coll on Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s ‘A Strange Story’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Sondeep Kandola

on The Picture of Dorian Gray |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Evan Mauro on Futurism in America |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Jeffrey Renye on Robert W. Chambers |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Work in Progress: |

Heather Braun on Salomé |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bibliography: |

Dissertations on the Anglo-Irish Gothic, 1973 – 1989

compiled by D.C. Rose after William O’Malley |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

James’s relationship to the cultures of Aestheticism and

Decadence is a fascinating narrative of youthful embrace, ambivalent

identification, disavowal and, in his late work, a rich and strange form of

assimilation. If his early dismissal of Baudelaire’s immorality suggested a

rigid distinction between an ethics of fiction and the poetics of decadence,

there is another sense in which the style of James late fiction exemplifies

the formal appetites of Decadence. In his classic definition of decadent

literary form, Arthur Symons diagnosed ‘an intense self-consciousness, a restless curiosity in

research, an over-subtilizing refinement upon refinement’. We might well say

the same of James tortured hypotaxis; the excessive refinement of

consciousness which is manifested some of the most baroque literary

experiments of the early twentieth century. But the Decadent opacity of his

late style is in marked distinction to the aesthetic openness of his youthful

impressionistic work. A reading of his beautiful early travel essays, later

collected in Italian Hours, is

enough to reveal that Walter Pater’s influence was fundamental on his ways of

seeing and reading. In this sense his novels from Roderick Hudson onwards are to some extent the diary of a

developing self-critique. In a series of early and middle phase works such as

The Portrait of a Lady, ‘The Author

of Beltraffio’ and The Tragic Muse, James

formulated a coherent critique of Aestheticism which subtly reiterated the

discourse of Paterian Hellenism and the aristocratic dandyism that would

flourish when Aesthetic Culture was transformed by the infusion of French

decadence in the Nineties. James’s complex relationship of affinity and *disavowal with these cultures was

obscured for some time, since moral critics such as F.R. Leavis and Dorothea

Krooke tended to construct a Manichean opposition between a moral James and a

dangerous Aestheticism. To some extent this opposition was reiterated in

Jonathan Freedman’s classic study, Professions

of Taste: Henry James, British

Aestheticism and Commodity Culture. But if Freedman still tended to

maintain an identification of Aestheticism with moral danger, he made the

important move of situating James’s dialogue with Pater and Wilde as the

reflection of an internal dialogue with his own aestheticising vision. In

this model, Aestheticism is a ‘contagion’ – an invasive principle which could

never be entirely contained. The physiological metaphor suggests the ways

that James’s complex and affinity and struggle would develop in the culture of

Decadence. The 1890’s witnessed a process of contagion and reciprocal

infection, where aesthetic discourse was increasingly marked by the traces of

its physiological sources. Rather than a taste to be refined, the bodily

matter of aesthetics was now visible as nervous excitability or, in more

extreme cases, the monstrosity that was figured in Dorian Gray’s portrait as

the other side of Aestheticism’s gospel of beauty. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Decadence and the

Late Novels of Henry James, Anna Kventsel’s densely textured and richly

perceptive study, these curious transitions in Decadent culture between

aesthetic consciousness, nervous embodiment and moral disorder are acutely

focused. One of the many virtues of Kventsel’s readings is a persistent

awareness of an often grotesque physicality in James’s metaphoric language

and vision of character. Kventsel demonstrate that the late Jamesian corpus

is deeply interfused with metaphors of psychic frailty, fluidity and

expansiveness, and an apparently contrary tendency towards containment and

reactive rigidification. Whilst her study gives little contextual account of

Decadent culture, it does provide a very suggestive theoretical focus on

physiological analogues for degeneration, deduced from Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor and Foucault’s The

Birth of the Clinic. This is not a

theoretically consistent study, however, and therein lies the root of its

originality and its occasional frustrations. The Foucauldian focus on bodily

discourses is only a starting point for a series of transitions; physiognomic

metaphors of degeneration are elided into the elucidation of ‘shadowy,

tortuous spaces, like the decaying rococo interiors in the Wings of a Dove, and the haunted, rotund and crooked

passageways of Fawns in The Golden Bowl’

(18). This is typical of the kind of gothic poetics which Kventsel applies to

Late James. Her focus on the psycho-physiognomy of minor characters and the

poetics of interior space tends to represent James as a kind of modern

Dickensian, a comparison that is accentuated by continuous and often perverse

deciphering of * name-puns. According to this gothicized version of James,

Kventsel deliberately usurps material from the late trio of novels to fit the

vampirism theory of The Sacred Fount.

One of the fruits of this perspective is a highly detailed sense of the

psycho-sexual symptomatics that *exists on a subliminal level in James’s

text, but on a more general level, Kventsel establishes a highly mobile and

condensed critical medium which is resolutely literary. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kventsel begins her study with Norbert Elias’s

socio-historical theory of the civilizing process – the cost of civilization

on sensuous experience and ‘affective action’. James’s protagonists undergo

an ‘ordeal of consciousness’ which ‘involves a destabilization of rigid

psychic defences, that is of internal mechanisms of screening and control,

instrumental to self-steering in the regulative channels of a culture shaped,

increasingly, by forces of the market and processes or cultural imperialism’

(2). This presents an ambitious remit, combining the discourses of an

emergent psychoanalysis with an attention to cultural dynamics and,

specifically, James’s relationship with the marketplace. This has already

been a significant feature in readings by Freedman, Ross Posnock and Richard

Salmon, all of whom are cited by Kventsel in her very sparing footnotes, but

her methodology is quite distinct from this post-Adornian wing of James

studies. The focus is sustained less in theory than by a highly attuned poetic

awareness which is constantly bringing together the registers of the

psycho-dynamic, the economic, the aesthetic,* and the religious. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In her reading of The

Ambassadors, Kvnetsel chooses to focus the religious and mythical

dimensions, setting up a sacramental and sacrificial vision of culture

heavily rooted in the vampire thematics of The Sacred Fount, and in an Augustinian concept of the Eucharist.

According to this schema, Strether’s trans-Atlantic narrative is an ‘inverted pilgrimage’ towards

sensuous communion, which ‘moves away from the desacramentalized reality

inherited *from the Puritans, to the palpable, passional Presence of Christ

in and as ourselves’ (9). In this hyper-civilised mimicry of pilgrimage, the

Parisian femme du monde occupies

the place of the sacred virgin, as well as being a Venusian figure for

sensuous flux. Such a mythical reading seems overdetermined when applied to

the single figure of Mme de Vionnet, but becomes increasingly suggestive when

applied to the image of |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The formal method bears fruit when Kventsel goes on to ask

interesting questions about the temporal experience of narrative and the

temporal condition of aesthetic consciousness. The propensity of aesthetic

consciousness towards experiences of merging are uncovered through the mythic

*image of the sea-change, and its tragic *parallel, the shipwreck, suggesting

the tenuous oscillation between aesthetic openness and abjection which

defines a number of James’s late protagonists. The most significant of these

figures is Milly Theale, and the reading of The Wings of a Dove is the dark heart of Kventsel’s book. It is

at this point that she begins to properly assess a relationship with

Aestheticism, beginning with Pater’s ‘Conclusion’, in which the call to

quickened consciousness via the recognition of mortality clearly prefigures

Milly’s condition. Kventsel goes on to uncover a dense undertexture of mythic

allusion – the image of Lorelei and the Wagnerian figure of the Rhine-maiden,

both of which hint at the shadow the novel casts across Milly’s immersive

aspirations, and the associated metaphor of the shipwreck, which is conflated

suggestively with Milly’s fragile yet defensively opaque ‘vessel of

consciousness’. From this metaphoric substratum, Kventsel develops a complex

and convincing argument about the contradictory nature of Milly’s subject

formation. On the one hand, Milly’s bid for passional experience is

constituted on an acute awareness of bodily existence and its frailty, yet

Milly frequently displays a reactive and protective ‘military posture’, in

which she experiences her own body as ‘an alien, rigidified, embattled

posture’ (64). Kventsel relates this psycho-physical duality to a fundamental

ambivalence towards the idea of character as action, or what we might call in

more recent terms, the performative assumption of identity as an experience

of bodily subjection. We might go further than Kventsel and relate this to

the condition of Paterian Aestheticism, where the call for a passionate

attitude of sensuous enjoyment sits uneasily with the idea of a diaphanous

personality who cultivates a peculiarly disembodied aesthetic subjectivity in

order to disrupt the assumption of any singular or habitual identity. Rather

than continuing to pursue the Paterian context she has suggestively

mobilized, Kventsel prefers to articulate Milly’s ambivalent corporeality in

terms of the different layers of religious iconography she accrues – at once

the immaterial angel or wind-spirited dove and, at the same time, an

incarnation and fall into embodied humanity. The extent to which Milly ever

does complete such a ‘fall’ is debatable. Kventsel reads the famous Alpine

scene as a demonstration of Milly’s renunciation of sublime elevation for ‘life

in the flesh’ (65), but the certainty of her ascription of a choice here begs

important questions. Can we ever ascribe a definitive sense of agency and

volition to Milly at this point, when what the scene primarily reveals is the

vicarious passions and fantasy life of Susie Stringham, the follower and apostle

who is condemned to live a vicarious life through Milly’s sublime example?

Does James’s method, at least in Wings, ever allow aesthetic subjectivity to

be contained and identified? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Some of *Kventsel’s central and most suggestive ideas

relate to the temporal condition of Decadence; first in her reading of the

circularity of Pater’s concept of aesthetic experience, and second, in her

sense of the way that the novel’s ‘symbolic matrices’ produce a static, or we

might say statuesque, aesthetic personality, which is defined precisely by

its estrangement from the temporality of that aesthetic experience which it

ostensibly embraces. Again in relation to Milly’s narrative, the novel’s

allusive and mythic texture creates an ‘attenuated’ presence which ‘blocks the

fluency of her fictional life’ (67). This is an important idea, since it goes

some way towards explaining an aspect of late James’s fiction which is not

perhaps addressed or confessed often enough – the uniquely frustrating

stylistic labour and the often tortuous demands it makes on the reader, who

is denied, perhaps systematically, the developmental pleasures of the bildungsroman. That James should deny

such pleasures precisely in those novels which are most concerned with

aesthetic bildung is one of the

most elliptical questions of his career, both in terms of his formal

development and in terms of his developing sense of the condition of

aesthetic subjectivity. Why, it needs to be asked, could James begin his

earlier treatment of the Aesthetic personality, The Portrait of a Lady, in a style not unrelated to the bildungsroman as we know it from

Goethe, whilst the deliberate opacity and static temporality of the initial

movements of The Wings of a Dove and

The Ambassadors appear to deny

either sympathetic identification or the avuncular ironic regard of his

earlier narrative position? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kventsel takes up James’s negotiation with the bildungsroman alongside a

consideration of his attitude to the romance genre. As Kventsel suggests, ‘Milly

is drawn to Europe in pursuit of bildung’

(112), but she is precisely

unable to experience the developmental time of bildung in her Symbolist retreat: the more she consolidates

herself in |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The study continues to elucidate these issues in the

concluding analysis of The Golden Bowl.

Adam Verver’s mid-life conversion to the gospel of art is one of James’s most

fascinating interior portraits of aesthetic subjectivity, and Kventsel

suggestively analyzes his decadent condition as a reactive but also

reflective relationship to imperialism and the new economies of culture

operating at the turn of the century. Adam’s interior rehearsal of Keats’s

Sonnet ‘On Reading Chapman’s Homer’ suggests a series of cultural

transitions: ‘Keatsian Romanticism is translated into fin-de-siècle

decadence, and the spirit of Regency England into the plutocratic spirit of

Gilded-Age America’ (146). The afterlife of Romanticism thus highlights the ‘imaginative

belatedness of Adam’s historical moment’ (145), and the consequence of this

belatedness is a hieratic and defensive emulation of the work of art itself.

Adam ‘embodies in his role as an animate museum piece the siphoning off of

subjectivity from the aesthetic sphere he has come to inhabit’ (150).

Kventsel demonstrates how this process of siphoning results in a petrifying

of the aesthetic process; like Milly’s journey from aesthetic openness to

symbolist rigidification, Adam’s increasing assimilation into the art-objects

he collects ‘recalls the compression of Milly’s trajectory’ (164). The

analogue is consolidated by the mutual trajectory of the two Jamesian

Aesthetes towards an angelic yet sacrificial position. Yet it is Charlotte

Stant, rather than Adam, who appears as the focal image of this reading;

uniquely and representatively opaque, like the texture of late Jamesian

fiction itself, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The sacrificial logic of narrative emerges as perhaps the

most forceful unifying theme in a study which orchestrates its diffuse

concerns more often through metaphoric architecture than linear theoretical

argument. This is a work which demands patience from the reader to discover

its originality; its poetic organization has a diffuse but accumulative effect.

In her Afterword, Kventsel arrives at larger assertions about the condition

of James’s fiction and the relation between aesthetic subjectivity, tragic

narrative and sacrificial mechanisms: ‘The late-Jamesian novel is […] an

imitation of the quintessential action of the mind, as it reaches past

patterns of sacrifice, dislodges the tragic, stretches and bends it and

loosens its bonds’ (210). This is Kventsel’s concluding sentence, and to some

extent it expresses a desire that James should point the way out of both

cultural decadence and a tragic model of character – towards Modernism,

perhaps, since Kventsel’s conclusion might be more applicable to Woolf than

James. Yet the study is very much the testament to a literature in

transition, attentive to its hieratic opacity and its poetic remainders as

much as its iridescent openness to impression. One of the strongest legacies

of Kventsel’s study is a style of thought – a critical sentence and

organization which is particularly appropriate to James’s late style, and the

peculiar density of its ethical, metaphoric and mythic registers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Andrew Eastham |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Patricia

Pulham, Art and the Transitional

Object in Vernon Lee’s Supernatural Tales (Aldershot and |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In her collection of essays, Belcaro, Vernon Lee gives a psychological definition of ghost: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

‘By ghost we

do not mean the vulgar apparition which is seen or heard in told or written

tales; we mean the ghost which slowly rises up in our mind, the haunter not